Introduction

Workforce housing is a concern for many Georgia policymakers and stakeholders. As home prices remain at near-record levels, renting is the only affordable housing solution in many communities. As such, apartments, townhomes and condominiums are an essential component of the housing market for many families and individuals. However, as the demand for housing grows, so too does the price of rent. This study seeks to determine how much of the cost of multifamily housing in Georgia is due to government regulation.

While building regulations for multifamily developments are necessary given the health and safety consequences inherent in high-density housing, it is also worth considering which of these regulations are simply adding cost without benefiting resident welfare. Regulatory costs are typically passed on to the consumer by increasing rents, which do not solely represent profit margins. Developers must demonstrate to lenders that rents will be sufficient to cover the cost of any loans, and even philanthropically oriented developers must break even on any affordable housing project.

Additionally, there are considerable deterrents for multifamily developers in both the private and public domain. These range from the increasing use of local government policies such as inclusionary zoning and rent control, to community residents stridently opposing the development of new apartment complexes based on what is commonly referred to as NIMBYism, or “not in my backyard.”

The purpose of this study is not to assert that all government regulation is bad or must be eliminated. Rather, it is important to assess the cumulative effect of all federal, state and local government regulations and identify potential areas that could be reduced. Every reduction in the cost of rent increases the ability to provide additional housing options in affordable price ranges. Regulatory costs also represent only one component in the rising cost of housing. Increased costs for land, building materials and labor are also drivers in the price of housing.

The Georgia Public Policy Foundation partnered with the Georgia Apartment Association to determine the cost of multifamily regulation statewide by surveying Georgia multifamily developers. The questions sent to each multifamily developer were the exact same as those provided by the National Association of Home Builders and National Multifamily Housing Council in the survey for their national study that was conducted in April 2022. These questions are included in the appendix.

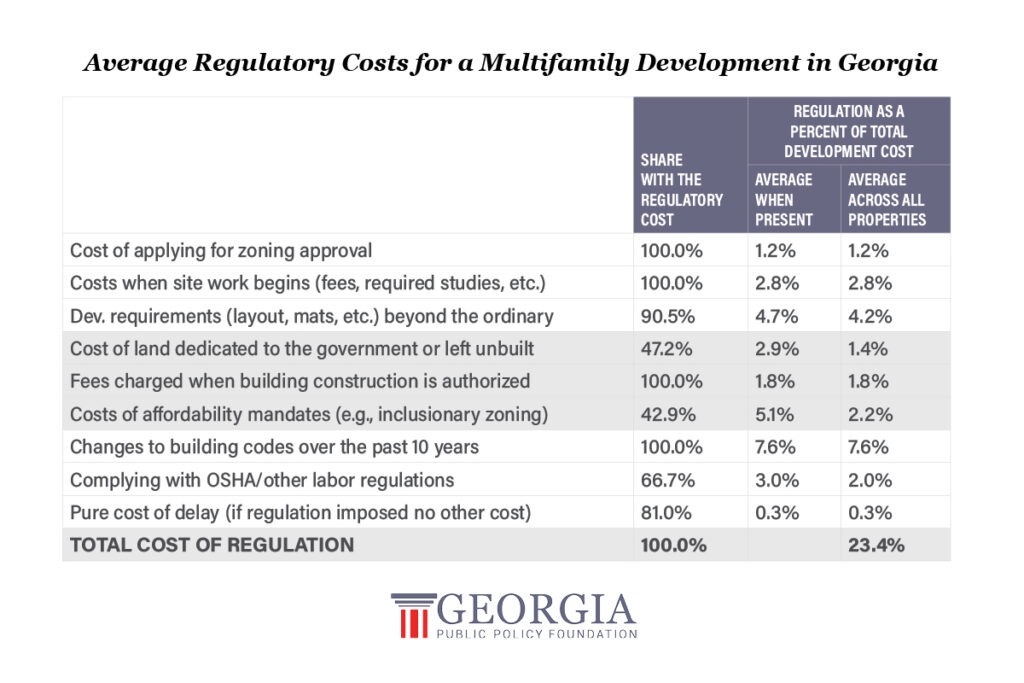

The research for Georgia finds that an average of 23.4 percent of the cost of multifamily housing can be attributed to federal, state and local regulation. The chart below provides a detailed analysis of the factors which contribute to the total cost of government regulation.

Methodology

The goal of the survey was to quantify the specific regulations and their cost for multifamily developers. In addition, developers’ experience with ancillary components that often obstruct the multifamily development process, such as neighborhood opposition, can affect the final number of units built and sometimes result in projects being stopped completely. These factors were also surveyed and are included in this report.

Twenty-one multifamily developers in Georgia provided complete and usable responses for the study. The survey was distributed by the Georgia Apartment Association and the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and conducted electronically during the fourth quarter of 2022. Answers from the respondents were combined with existing public data to calculate the total development cost. The description of the assumptions used in the calculations, along with the questions for the multifamily developers, are in the appendix.

The Georgia Public Policy Foundation and National Association of Home Builders previously partnered to study the cost of regulation to build a single-family home in Georgia. It was published in January 2022 and found that regulations on average added 26.9 percent to the final price of the home.

One area this study did not research but may address in future iterations is the cost of government regulation for developers that acquire and renovate dilapidated multifamily buildings. While this often represents an easier path to providing adequate multifamily housing than new developments, in many circumstances the refurbishing process presents more regulatory burdens.

Total Cost of Regulations

Understanding Table 1 The last column of the table shows the averages across all multifamily developments in the survey, even those not subject to a particular type of regulation (i.e., the “zeroes” are averaged in). The column to the left of that shows average costs calculated only for those properties that are subject to the regulation. Note that because each percentage in the “Average When Present” column is calculated for a different set of properties, the rows in that column do not add up to the total. The primary reason for including this column is so readers interested in the comparatively uncommon regulations—such as requiring developers to leave some of their land unbuilt and affordability mandates such as inclusionary zoning—can see how costly these regulations tend to be when they are present. The other categories of regulation in the table are widespread. For them, the differences between the “Average When Present” and “Average Across All Properties” columns are negligible.

Table 1 provides additional information on the specific regulations that contribute to the cost of multifamily housing. Changes to building codes over the past 10 years (7.6 percent) is the highest cost of regulation for multifamily housing.

The lowest cost of regulation is the pure cost of delay (0.3 percent), which is consistent with the lowest cost of multifamily regulation in the national study (0.5 percent). The complete regulatory process, and the costs incurred at each step, are further explained in detail.

Before site development or construction can begin, the developer must ensure the land is zoned for multifamily use. Each developer that was surveyed reported having to pay for zoning approval, which added 1.2 percent to the cost on average. This step in the regulatory process includes fees paid to the local government to begin the approval process. It also can include supplemental costs such as environmental impact studies conducted by private consultants.

Once the developer has secured approval for the project, local governments also require an array of additional fees and studies. Each respondent reported encountering these costs, which add 2.8 percent to the cost of multifamily housing. One example of regulatory costs when site work begins includes development impact fees, which in Georgia can range in cost from $229.15 to $7,757.85 per unit.

Ninety percent of respondents reported dealing with architectural development requirements. These were defined in the survey by asking developers if they were required to use building materials beyond what they would have ordinarily used without the local government mandate. Examples of this include energy-efficiency upgrades or aesthetic design requirements for facades. These architectural design standards added 4.7 percent to the total cost in Georgia.

Sometimes developers are required to dedicate a portion of the land for greenspace or set aside parcels of the development for new parks or schools. Less than half (47.2 percent) of the respondents reported dealing with these regulatory burdens, which added 2.9 percent to the cost of multifamily housing when present.

Once the final site preparation is completed, local governments often assess additional fees before authorizing the construction process. Examples of this include building permitting fees or additional utility hook-ups. Every respondent reported paying these costs, which added 1.8 percent to total development costs.

Affordability mandates are increasingly popular among local policymakers seeking ways to address the cost of housing. The most common is inclusionary zoning (IZ), in which developers are incentivized or mandated to set aside a certain percentage of units at below-market pricing.

Atlanta was the first Georgia city to implement an inclusionary zoning policy. It was enacted in 2018 and has since expanded into additional neighborhoods in recent years. Atlanta’s IZ Policy requires developers of all residential rental developments consisting of 10 or more new dwelling units to set aside at least 10 percent of their units for incomes at or below 60 percent of Area Median Income (AMI) or 15 percent of their units for incomes at or below 80 percent of AMI. They can also choose to pay a one-time in-lieu fee rather than setting aside IZ units.

Brookhaven was the first jurisdiction to implement a citywide inclusionary zoning policy, while Decatur and Athens-Clarke County have also enacted inclusionary zoning policies in recent years. City officials in Savannah have debated implementing an IZ ordinance for over a year but have not yet been approved one.

Two-thirds of multifamily developers in Georgia reported that their typical projects were built in jurisdictions that utilize inclusionary zoning. In some cases, incentives are adequate and result in no net increase in costs. However, 42.9 percent of respondents reported building in jurisdictions where IZ not only existed, but added significantly to the cost of the projects. In these cases, IZ added 5.1 percent to total development costs (2.2 percent when averaged across all projects in the sample). Among the two-thirds of developers who built in jurisdictions with IZ, the average increase in rents on market rate apartments as the result of IZ was 7.3 percent. This has the potential to price some middle-class families out of the new developments.

Changes to building codes are consistently the highest cost of regulation for many home builders. While there are legitimate goals within building code changes to protect resident safety and structural integrity, there are also aspects within the building code industry that have evolved and expanded beyond public health. Members of building code commissions often represent and advocate for specific industry interests, such as certain building materials or workforce requirements which can add unnecessary costs. In addition, federal policymakers also advance political agendas such as sustainability initiatives through the development of building codes. Each developer reported dealing with this regulation, which added 7.6 percent on average to the cost of multifamily developments.

Developers must also comply with labor regulations during the development process, such as Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requirements. While workforce protection measures are essential, the NAHB has previously noted that certain OSHA policies drive up development costs without offering additional protection for workers. Labor regulations affected 66.7 percent of respondents, which added 3.0 percent on average to the cost.

The final regulation measured is the cost of delay for compliance on the typical project. Eighty-one percent of multifamily developers reported experiencing these delays, which added 0.3 percent on average to total development costs. While this is the lowest estimated regulatory cost, it is important to consider that many construction loans are dependent on completion of the project. As interest accrues during the delay, those added costs are ultimately borne by the renter.

Rent Control and Inclusionary Zoning

Rent control is a policy which limits the ability of the landlord to raise rent above a certain price. In Georgia, local governments have been banned from enacting rent control regulations for nearly 40 years. State law says that “No county or municipal corporation may enact, maintain, or enforce any ordinance or resolution which would regulate in any way the amount of rent to be charged for privately owned, single-family or multiple-unit residential rental property.”

However, legislation was introduced in the Georgia Senate in 2023 which would repeal the state ban on rent control, allowing local governments to enact their own policy. While the bill did not receive a hearing, the concept of rent control has been supported publicly by local policymakers, including the mayor of Atlanta. Given this, we surveyed Georgia multifamily developers to gain an understanding of their willingness to build in jurisdictions where the policy would be in effect. Nearly 80 percent of respondents said they would avoid building in jurisdictions with rent control.

We also surveyed Georgia multifamily developers on their willingness to build in jurisdictions that enact inclusionary zoning policies. Unlike rent control, local governments in Georgia can enact these policies.

The effect of these mandates often creates uncertainty regarding the financial feasibility of a project, with both short-term and long-term implications. As more local governments consider this course of action, it is notable that almost 89 percent of developers said they do not avoid building in areas that require inclusionary zoning.

Neighborhood Opposition

Neighborhood opposition is certainly not a new phenomenon when it comes to multifamily development. Over 90 percent of developers surveyed have experienced neighborhood opposition to new multifamily development, often in public hearings by citizens opposing attempts to rezone property for development. Developers have also been subject to lawsuits trying to stop multifamily development in their neighborhood. Delays due to neighborhood opposition added 1.8 percent on average to development cost. It also delayed completion of the project by an average of 5.4 months when it occurred.

Conclusion

The national study conducted found that government regulations contribute 40.6 percent on average of a project’s development costs. While the average for Georgia is considerably lower, adding 23.4 percent in total federal, state and local regulatory costs is significant when assessing the marginal rent increases that many households earning the area median income can withstand. As interest rates continue to rise, it will further affect the ability of many lenders and developers to provide multifamily housing at prices that meet the demand for workforce housing.

Government regulation is not all bad or should be eliminated. Nor is government regulation the sole driver of rising housing costs. But it is one factor that policymakers can directly address if they wish to increase the availability of workforce housing. With the rise in policies such as inclusionary zoning and rent control, policymakers should also consider their ability to lower costs during the development of these projects as well.