Executive Summary

Open enrollment is a system through which K-12 students can transfer from one public school to another. While this program is popular and expanding throughout the country, its potential is still not realized, including in Georgia. While Georgia law allows transfers to and from public schools within district boundaries, there are still numerous legal, financial and bureaucratic limitations on academic freedom. This report provides an overview of the open enrollment environment in Georgia and how it compares to other states, highlights issues with transparency and data reporting, and offers recommendations on how this category of school choice policy can be strengthened.

Background

One of the most popular and intuitive forms of school choice is a student’s opportunity to transfer from one public school to another. While perhaps not the most publicized battleground of educational freedom at this moment, the national landscape is varied and reflects conflicting opinions on how open the K-12 transfer process should be. Some states give students the option to transfer to schools within their local school district of residence, some give the option to transfer to other districts, and still others give both options – or neither. This report reviews the landscape of open enrollment transfers in Georgia at the state and district levels, as well as how the Peach State’s environment compares to other states. In addition, the report highlights data collection and publication among states and Georgia districts.

A good place to start is asking what a state aims to achieve by allowing transfers. Whether inter- or intra-district transfers, the rationale is the same as that for school choice at large: Students and their parents should be allowed to choose the learning environment that best suits them. If that option is a different public school from the one they currently attend, they should be afforded the freedom to transfer without arbitrary boundaries.

Transparency is a related matter. Despite an expanding set of options for students across the country, the vast majority of families still send their students to traditional public schools. Georgia’s parents should be informed of their options, as well as how, and whether, the transfer process works.

In addition to being philosophically consistent with most school choice arguments, implementing open enrollment has shown positive impacts and sees broad popular support.

A 2023 report from EdChoice featured interviews with district administrators from eight different states. These administrators reported that open enrollment encouraged them to innovate in order to attract and retain students who might otherwise go to private schools, charter schools or a different public district.

The concept of competition as a driver of school improvement is also supported by a 2023 report by the University of Chicago’s Becker-Friedman Institute for Economics. This report analyzed the “Zones of Choice” program, an initiative of the Los Angeles Unified School District that introduced school choice to limited areas of the city. The study found that open enrollment transfer programs can improve quality through competition, and that the lowest-performing schools saw the most improvement.

ExcelinEd’s summary of open enrollment policies takes it even further. The authors point out positive impacts and widespread national support, but also highlight exclusionary district laws and boundaries. Referring to a report by national public school watchdog Available to All, they describe an “unjust framework that assigns schools based on geography, not what students need, often placing the highest quality options out of reach for lower-income and marginalized students.” This comment echoes a statement from EdChoice on the current state of open enrollment policies, “Using district lines to determine where a child goes to school is a 200-year-old mistake that has resulted in racial and socioeconomic segregation in U.S. public schools.”

There is no national standard for open enrollment; states have different and unique procedures. Georgia is one of 13 states that allows for within-district transfers. Previously, Georgia students were only able to transfer to a school outside their districts if both the receiving and origin schools agreed. However, with the 2024 passage of Senate Bill 233, only the receiving school now needs to sign off on the transfer. Transfers are only allowed in any case if the receiving institution’s available capacity allows for it. Many school districts do not allow any students from other districts to transfer in as official policy.

Open Enrollment in Georgia

Georgia is typical of most states in that its Department of Education does not collect data on K-12 transfer students. In fact, only three states (Kansas, Oklahoma and Wisconsin) feature state agencies that track these data. The only place to find this information in Georgia is at the district level, and the only data relevant to this report that districts are legally required to report are seating capacity numbers. Many districts do not keep track of student transfers at all.

For this report, the Georgia Public Policy Foundation reached out to 69 of the largest school districts in Georgia and received 21 responses.

Some districts collected all data that were relevant to their transfer processes, some did not collect any, and most respondents had some but not all data. Additionally, some district employees had the relevant data on hand and responded promptly and thoroughly to the Foundation’s request, whereas other districts needed to involve several departments to collect the data. Typically, when this happened, the Foundation was asked to submit a formal records request, which takes more time and often costs money. While we recognize the size and structure of a district’s administration generally determines the ease and quickness of data collection, we felt it important to note this part of the process as it is another barrier to transparency. Given the lack of state collection and district reporting, this report’s research also sought to determine how quickly and easily data can be found.

It should be noted that this report is not an audit or analysis of school districts and their employees and administrators. After all, capacity is the only information that districts are required to report. However, transfer applications are almost certainly documented somehow, and what districts decide to do with those documents often determines how readily available the information is.

The Foundation asked the following questions of Georgia school districts concerning the most recent available school year:

- How many within-district students in the district have applied for an open enrollment transfer? How many of these applications were denied, and what were the reasons for denial?

- How many out-of district students have applied for a cross-district open enrollment transfer to a district school? How many of these applications were denied, and what were the reasons for denial?

- What is the seating capacity for each school in the district?

- How many within–district transfer students participate in a Free and Reduced Lunch program?

- How many within-district transfer students are English Language Learners?

The first three points address the basic question of how easy it is to use the transfer system in a given district. Seating capacity was requested because it is the most common reason for application denial.

The final two questions were asked in search of additional characteristic patterns among transfer students. While these descriptors are not exact reflections of socio-economic status and demographics, respectively, they are frequently tracked by school districts as students that often require additional educational means. It could be reasonably assumed that students who fit this category would be more likely to face educational hardship, and therefore more likely to request a transfer. Higher numbers in these categories would warrant further study.

The Georgia Public Policy Foundation reached out to most school districts via email and had several follow-ups via phone call. Because nearly half of Georgia’s K-12 students attend the 10 largest districts, an emphasis was placed on larger districts. For example, counties with only one option for elementary, middle and high school were typically left out of this report.

We received 21 responses, although some responding districts were unable to provide the data we requested.

The districts that responded and were able to at least provide the number of accepted and denied applications for the most recent school year accounted for approximately 547,000 students, almost a third of Georgia’s K-12 public school students. These districts included Bibb County, Burke County, Carroll County, Cherokee County, Clayton County, Cobb County, City Schools of Decatur, DeKalb County, Fayette County, Fulton County, Glynn County, Houston County, Paulding County and Walton County. Combined, these districts reported:

- 25,826 total applications

- 20,448 applications accepted

- 5,378 applications denied

While this might suggest that about four out of five transfer applicants are accepted, that is not quite an accurate picture. Districts differ from one another both in how they track transfers and in how their transfers are processed. For example, some districts reported zero applications denied because their schools at enrollment capacity do not even make applications available – meaning students who wished to transfer to these schools were effectively denied from the get-go. The following examples illustrate some of the differences and idiosyncrasies between districts.

Examples

Glynn County was an example of a school district that keeps track of relevant data and responded quickly and concisely to the Foundation’s requests.

- For the 2023-24 school year, Glynn County received 328 intra-district transfer requests. Of these, 256 were accepted, and 72 were denied. Reasons for denial included capacity, attendance, behavior and grades.

- Glynn County received 50 out-of-county requests, and only one was denied for behavior.

- Of all waivered students in Glynn County (not limited to the 2023-24 school year), 724 have Free and Reduced meal statuses and 67 students were enrolled in or have exited English Language Learning.

Walton County also tracked most relevant data and responded promptly via email.

- Walton County received 455 intra-district applications and denied 29 of them. The district did not sort the reasons for denial, but a district representative said the primary reason was inadequate proof of residency or a parent/guardian not confirming a selection (i.e. changing their mind and not telling the school system).

- Walton County does not accept transfers from students living outside the district.

- Walton County submitted its seating capacity (a total of 15,932 students) broken down by each school.

- Walton County transfer students include 203 participating in Free and Reduced Lunch programs and 0 English Language Learners.

As mentioned earlier, there is no standardized manner of collecting and publishing these data, so even schools that thoroughly track transfer data may have a different methodology for doing so. One example is Carroll County, which tracks data relevant to our survey, but does not separate inter-district from intra-district transfers. It also does not track the reasons for denial.

- Carroll County received 573 transfer requests in the 2023-24 school year. It approved 393 applications and denied 180.

- Carroll County also published its capacity broken down by school (the total was 18,100).

- Of the 1,833 waivered students enrolled in Carroll County Schools, 746 participate in Free and Reduced lunch and 19 participate in English Language Learning.

Fayette County responded with a similar set of data, however it also reported how many denied students participated in Free and Reduced Lunch programs and English Language Learning, in addition to approved transfer students.

- Fayette County received 172 transfer requests. It approved 150 and denied 22.

- Of the approved, 55 participated in Free and Reduced lunch and none were English Language Learners.

- Of the denied, six participated in Free and Reduced lunch and two were English Language Learners.

Some Georgia districts only reported intra-district applications and denials (often because the given districts do not accept inter-district transfers). Examples of this included Bibb County and Cobb County.

- Bibb County received 641 applications. Of those, 223 were approved and 418 were denied due to lack of space.

- Cobb County received 1,605 applications. It approved 1,466 and denied 139, all due to capacity limitations. A Cobb representative noted that the denied students were subsequently placed on a waiting list for their requested school.

In addition to differences in reporting, districts also frequently differed in how they administered transfer requests, which further complicates cross-district data analysis. The most common example is the aforementioned practice of not making applications available for schools at capacity. This results in transfer rates being at or near 100 percent, given that no denials would be issued for capacity reasons. While this procedure likely saves time, it is not as common and presents another issue for data collection and interpretation.

Example districts include Paulding County and Houston County.

- Paulding County accepted all of its 228 intra-district transfer applications, as its transfer option was only available for schools with available seating. Paulding received zero cross-district applications.

- Houston County accepted all six intra-district transfer applications. It did not receive cross-district requests, although it does accept them under certain circumstances.

Houston County is a unique case and worth highlighting here. Its low number of requests can be partly explained by the very low capacity in its schools. However, this district also has an additional provision to account for the personnel stationed at Robins Air Force Base. Houston County utilizes legislation that gives active military service members who live on base the option to request any school within the district based on space availability.

- Houston County received 51 such transfer requests and accepted all of them.

Just as different features of local education bureaucracies can affect the depth (and existence) of desired data, it can also affect the ease with which it is procured. Some district representatives were able to answer all of the Foundation’s requests via email. Others, meanwhile, required formal open records requests to be filed. While not every district charged money for these requests, some did; costs ranged from a few dollars to over $100. Response times varied.

Similarly, some districts gave limited answers for no charge, but greater detail would have required payment. Bibb County, for example, gave the above information free of charge, but would have required payment to answer questions about Free and Reduced Lunches and English Language Learners, apparently because producing these data would have involved multiple departments within the district. Carroll County presented its data without separating in-district transfers from out-of-district transfers, and offered to charge for the work it would have taken a district employee to sort through each transfer to separate the two categories.

None of these instances is atypical of data requests such as this one. However, it is worth mentioning as part of the research process because it is a clear limitation on the transparency of the transfer process. Even if the data are available, it costs time and money to put it all together.

Further compounding that issue, some school districts do not track or collect any data at all pertaining to transfer students. This is especially concerning in the case of Gwinnett County – the largest school district in the state with over 180,000 K-12 students. Not only does Gwinnett not collect any data on open enrollment transfers, most of the available data on the district’s strategic waivers webpage (to which the Foundation’s search was directed by a district official) was nearly 10 years old.

While again, a district’s lack of open enrollment information does not violate state law, it further complicates analysis of school choice policies. Gwinnett County holds a significant enough portion of Georgia students that this creates a meaningful transparency issue.

The National Environment

Georgia’s system – and its local systems – of student transfers leave much to be desired both in terms of available choices and in data collection. However, Georgia’s shortcomings are common among American states. While permitting transfers has become more popular over the past few years, the majority of states’ laws on open enrollment do not allow it to work to its full potential, and most states do not report adequate data.

Last year, the Reason Foundation released a report that examined every state’s open enrollment policies. The authors judged those policies on five criteria:

- Does the state allow for within-district transfers?

- Does the state allow for cross-district transfers?

- Does the state’s state education agency report transfer data?

- Do the state’s local school districts transparently report transfer data?

- Is public school free for all students in the state?

Currently, Georgia meets only one of those criteria: within-district transfers. Although Georgia’s districts may opt into cross-district transfers, many do not allow them. No states met all five of the Reason Foundation’s criteria, and only six states met four of the five.

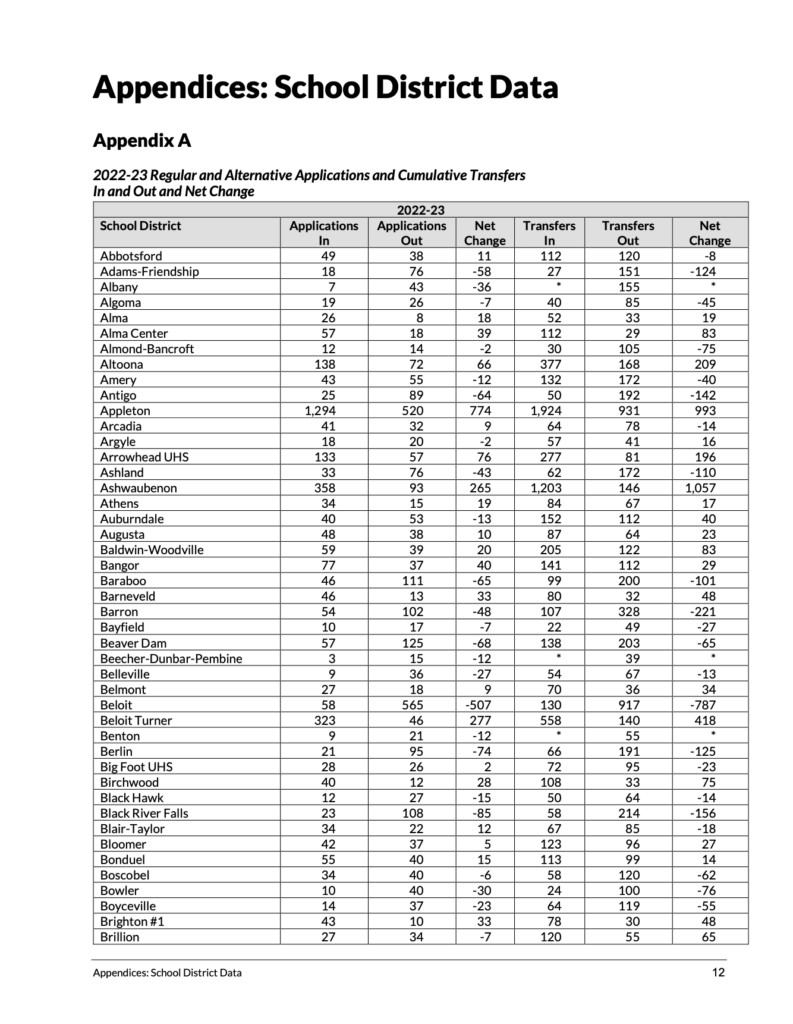

A particularly interesting finding from the Reason Foundation’s report is that only three states report transfer data at the state level. A worthwhile example of good reporting is found in Wisconsin. While Georgia and Wisconsin have different transfer systems in place – Georgia allows for intra-district transfers and not inter-district transfers, while Wisconsin permits the opposite – the Badger State’s example of data collection is exemplary and worth highlighting. A Wisconsin statute requires its education agency, the Department of Public Instruction, to submit annual reports that include:

- “The number of pupils who applied to attend public school in a nonresident school district under the full-time open enrollment program”

- “The number of applications received under the regular and alternative application procedures, and for the applications received under the alternative application procedure, the number of applications received under each of the criteria listed under the alternative application procedure”

- “The number of applications denied and the bases for the denials”

- “The number of pupils attending public school in a nonresident school district under the open enrollment program, as well as the number of pupils. The department shall specify, separately, the number of pupils attending public school in a nonresident school district whose applications were accepted under the regular application procedure and the alternative application procedure, and for the applications submitted under the alternative application procedures, the number of pupils attending under each of the criteria listed under the alternative application procedure.”

The statute that requires these reports was enacted in 2011, but extensive reporting on the DPI’s website dates back to the late 1990s. Wisconsin’s example demonstrates that states have the capability to give a clear and complete picture of the open enrollment environment; they can describe how well the system works for the people who opt into it. They can also do this free of charge, avoiding the financial and time constraints the Foundation met in its open records requests.

Recommendations and Conclusion

Both for the sake of principle and pragmatism, Georgia should provide a higher level of choice to K-12 students. From data collected from local school districts, we can see that students who apply to transfer within a school district are able to do so in most cases. Of the school districts that reported their data to the Foundation, only Bibb County, Clayton County and Fulton County denied more transfers than they approved in the most recent school year. Despite this positive result, students’ choices of public schools are still arbitrarily limited. Also, as referenced in the Paulding County example, the number of students who want to transfer is not always represented in the number of applications.

Allowing within-district transfers means not confining students to their ZIP codes. It is therefore intuitive that the next step would be to no longer confine them to their counties. The passage of SB 233 means students no longer need their origin districts to agree to a cross-district transfer, but many districts still do not allow students to transfer in from other districts. Georgia should require all school districts to participate in statewide cross-district and within-district open enrollment.

Whether or not Georgia expands its transfer program, Georgians deserve a higher level of transparency. This can be achieved by district reporting to the Department of Education, which should publish that information. Standardizing the process of data reporting and making the relevant data available in one place would make it accessible to all Georgians at no charge. It would allow for comparisons between schools and districts.

Wisconsin’s example provides a good format for replication in other states. Georgia’s state-level reporting should at least include transfers in and out of each school, along with net change. It should also include reasons for denied applications. While many schools do not currently track reasons for denial, it is an important part of the process and can reveal non-apparent details about local schools. For example, rejecting a transfer student because of a verified lack of classroom capacity is one thing. However, if a school or district sees high numbers of rejections based on behavior, state agency reporting would highlight behavioral issues. If a district issues several denials because of incomplete applications (as Walton County did), it would tell a different story about the transfer process than simply having full classrooms.

Although tuition was not included in the Foundation’s research for this report, it is yet another barrier to school choice. Even if a student is allowed to transfer, Georgia is one of 26 states that allow their public schools to charge tuition to transfers. We echo the Reason Foundation’s recommendation that public school should be free to all Georgia students.

Open enrollment is a popular program that has demonstrated positive outcomes for both students and schools. The unfortunate reality is that Georgia is a typical state in that its transfer laws are limited in the opportunities they provide. Furthermore, the extent of reporting currently gives us only pieces of information about how well the program works. School choice should be expanded, and students should not be limited by district boundaries or the arbitrary financial burdens added when they leave their districts.

Transparency also needs improvement. The Foundation has long fought for transparency in education reporting, especially on the part of the Georgia Department of Education. Even though adequate reporting on transfers throughout the country is rare, it can be done. Access can be expanded, and transparency ensured, to the benefit of students and families. Georgia should work to put those pieces together into a more open and cohesive student transfer policy.