The federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) expanded Medicaid to all individuals under age 65 with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). The U.S. Supreme Court ruled, however, that states are not mandated to expand Medicaid coverage. As of January 2014, Georgia and 23 other states had chosen not to expand Medicaid.

Although most reports have indicated 650,000 uninsured individuals are impacted by Georgia’s Medicaid expansion decision, approximately 240,000 have incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the FPL and will be eligible for subsidies in the exchange. That leaves about 410,000 who have incomes below the poverty level but are not currently eligible for Medicaid or other subsidies.[1] So by refusing to expand Medicaid, more than 200,000 uninsured Georgians will receive heavily subsidized, much better quality private insurance.

The focus then becomes the remaining group of 410,000 comprised of able-bodied adults with incomes below 100 percent of FPL. The real debate should revolve around how best to ensure access to health care for these individuals.

The challenges of expanding Medicaid eligibility include uncertainty regarding funding and costs, questions regarding the effectiveness of the Medicaid program and the impact on existing Medicaid recipients.[2]

Uncertainty of federal funding

The federal government has promised to pick up 100 percent of the cost of these newly eligible Medicaid recipients for the first three years, eventually declining to 90 percent. This compares to a 65 percent match for Georgia’s existing Medicaid population. The total cost of expansion is more than $2 billion a year, which is not a trivial amount. As Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute puts it, “Ten percent of a really big number is still a really big number.”[3]

Recent evidence indicates promises of federal funding should be viewed skeptically. President Obama’s 2013 budget proposed shifting more than $50 billion of Medicaid costs onto states,[4] and federal reductions in Medicaid consistently come up in budget talks.[5] From a political perspective, entitlements are extremely hard to scale back once they are expanded. There is also nothing to prevent the federal government from imposing “maintenance of effort” requirements, as they have in the past, to prevent states from reducing eligibility.

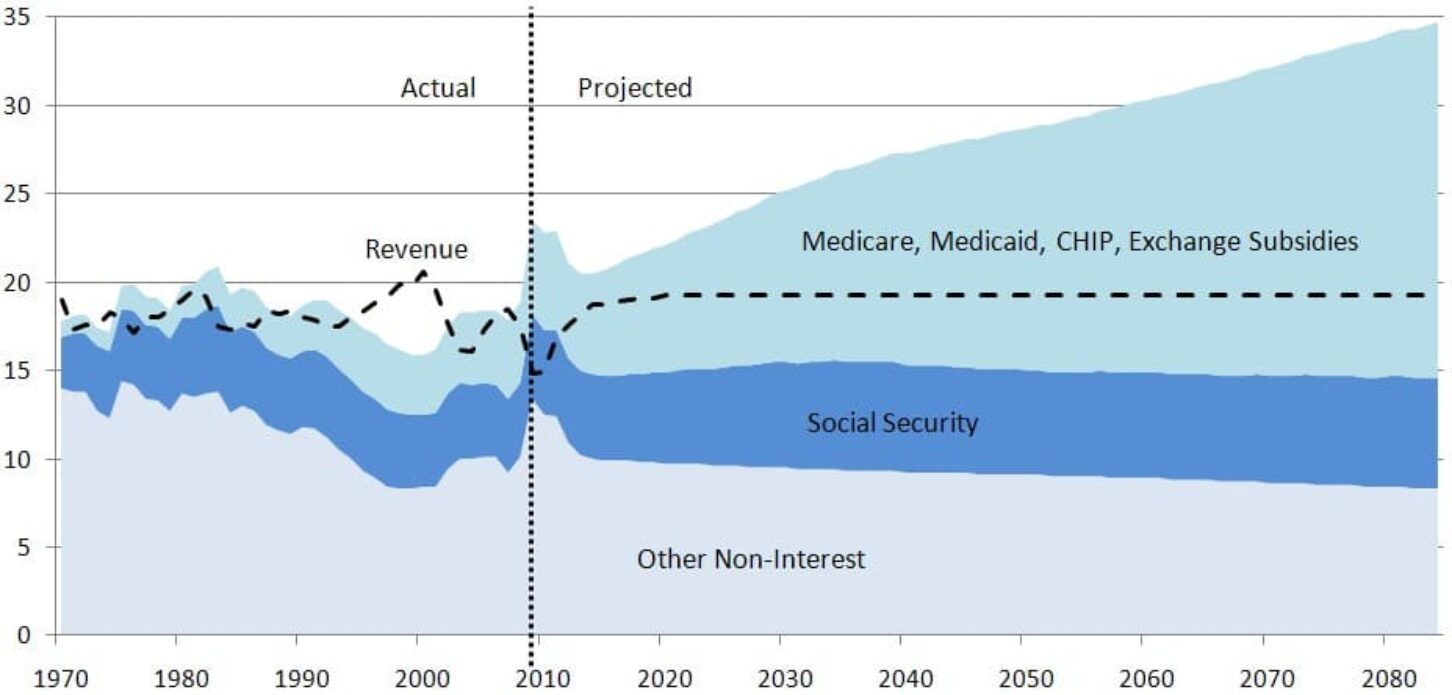

The chart below shows the unsustainability of federal health care spending. The Congressional Budget Office projects health care spending to increase dramatically while non-health care spending stays relatively constant and revenues (dotted line) revert to their long-term average of 18 percent of GDP.

Spending by Category in CBO’s Alternative Fiscal Scenario (Percent of GDP)

Perverse incentives

Even if the federal government maintains the promised matching rate of 90 percent, the difference in matching rates creates perverse incentives: Reducing eligibility for able-bodied adults creates $1 of state savings for every 10 recipients who lose benefits, while reducing eligibility for low-income mothers creates $1 of savings for every three individuals who lose benefits. This puts budget writers in a very difficult position during the inevitable next recession.

Uncertainly regarding enrollment of individuals already eligible for Medicaid

Even if Georgia declines to expand Medicaid, the cost of implementing PPACA is projected to increase state costs by more than $100 million. If a large number of currently Medicaid-eligible individuals sign up, that could add another $115 million to annual costs. It would be wise to determine the source of this funding and the effect on Georgia taxpayers before making a decision to expand Medicaid rolls.

The higher federal match rate only applies to newly eligible enrollees in Medicaid; Georgia will continue to pay roughly one-third of the cost of every currently eligible enrollee that signs up. The Urban Institute estimates there are 159,000 adult, low-income Georgians who are currently eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled.[6] The Georgia Department of Community Health assumes fewer than 25,000 (a little over 15 percent) of these Georgians will sign up for Medicaid; this is referred to as the “woodwork effect.” But what if they are wrong? Millions of dollars are being spent around the nation to encourage individuals to sign up for health insurance. If the signup rate is closer to 75 percent, that is more than 119,000 new enrollees and additional annual state costs. In addition, the state estimates only about one-third of the 176,000 children who are currently eligible for Medicaid will enroll, which could also be a low estimate.[7]

Medicaid is already crowding out other state priorities

Initially, the federal government would bear all of the costs, but some Medicaid expansion costs would ultimately fall to the state. As in other states, the Medicaid program is consuming an inordinate share of the state’s revenue, diverting money from other important state priorities such as public safety, education, and infrastructure maintenance and improvements. As the chart below shows, Medicaid now takes one of every five state dollars and its share of the budget has almost doubled over the last decade. Georgia is struggling to fund current Medicaid recipients. A provider fee increase was required last year to raise $689 million to fill a Medicaid funding shortfall.[8]

| $ Growth | Share of Budget | Change in Share of Budget | |

| PK-12 Education | 27% | 40.4% | 0.8% |

| University System | 4% | 9.2% | -1.8% |

| Technical College System | 14% | 1.7% | -0.2% |

| Health Care | 103% | 20.5% | 7.9% |

| Debt Service | 2% | 4.8% | -1.1% |

| Everything Else | 1% | 23.5% | -5.7% |

Negative impact on access for existing vulnerable populations

A third of Georgia doctors already refuse new Medicaid patients.[9] Adding several hundred thousand more recipients to the program will further strain the system and could negatively impact existing Medicaid recipients: the elderly, the disabled, pregnant women and children.[10]

Increased emergency room use

Excessive use of expensive emergency room care is one reason often cited for the need for Medicaid expansion. But an extensive study in Oregon showed Medicaid recipients utilized the emergency room 40 percent more than the uninsured.[11] A majority of the visits were for non-emergency care. This aligns with other studies showing charity care costs actually increased in states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility such as Maine, Arizona and Massachusetts.[12]

Very little, if any, improvement in health status

The Oregon study showed no statistically significant improvement in physical health outcomes for Medicaid recipients versus the uninsured. The study showed better diagnosis and treatment for depression, but Forbes’ Avik Roy notes that this could be accomplished at a fraction of the cost of Medicaid coverage.[13]

Crowd out. As much as a third of the newly insured could be individuals who already have private insurance. According to the Census Bureau,[14] 222,000 Georgia adults under age 65 with income below 100 percent of the FPL are currently covered by private insurance. Even if their policies are not cancelled by ObamaCare regulations, these individuals (or their employers) would be tempted to drop their private insurance in favor of “free” Medicaid coverage.[15] That is one reason why the uninsured rate did not decline in many states that have expanded Medicaid.[16]

Cost effectiveness. By one estimate, the uninsured in Georgia create unpaid bills equal to $2.8 billion, or an average cost of $1,500 per uninsured person, much of it covered by taxpayers.[17] The Georgia Department of Community Health estimates new Medicaid enrollees would cost more than $5,800 per person. If the results of the Oregon study are accurate, Medicaid expansion would nearly quadruple government spending, produce scant improvement in their health outcomes and increase emergency room usage.

Doing nothing is unacceptable, but Georgia can certainly develop a better plan. Georgia is projected to lose $77 million of federal funding for safety net hospitals between 2015 and 2017. The cuts were originally scheduled to begin in 2014, but were delayed for one year. This gives us a window of opportunity to propose a better solution. An upcoming study will examine the alternatives.

[1] A new report from the Kaiser Family Foundation points out that 409,350 Georgians will fall into the “coverage gap” if the state refuses to expand Medicaid (Table 2 in the report, http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/). Large federal subsidies will be available to assist families with incomes above the Federal Poverty Level purchase private insurance, which means that the number left uninsured if Georgia does not expand Medicaid is 409,350 instead of the 650,000 that most news organizations have reported.

[2] “Expanding Medicaid: The Conflicting Incentives Facing States,” Mercatus Institute at George Mason University, http://mercatus.org/expert_commentary/expanding-medicaid-conflicting-incentives-facing-states

[3] “Tanner: No miracle in Medicaid expansion,” by Michael Tanner, Virginian Pilot, http://hamptonroads.com/2014/02/tanner-no-miracle-medicaid-expansion

[4] “Fiscal year 2013: Cuts, consolidations and savings,” Office of Management and Budget, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2013/assets/ccs.pdf

[5] “Proposal to establish federal Medicaid “blended rate” would shift significant costs to states,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, http://www.cbpp.org/files/6-24-11health.pdf

[6] “Opting Out of the Medicaid Expansion under the ACA:

How Many Uninsured Adults Would not Be Eligible for Medicaid?” Urban Institute, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412607-Opting-Out-of-the-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA.pdf

[7] “Medicaid/CHIP Participation Among Children and Parents,” Urban Institute, p. 6, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412719-Medicaid-CHIP-Participation-Among-Children-and-Parents.pdf

[8] http://gov.georgia.gov/press-releases/2013-02-13/deal-signs-provider-fee-bill-ensures-hospitals-critical-medicaid-funding

[9] “Study: Nearly A Third Of Doctors Won’t See New Medicaid Patients,” Kaiser Health News, http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2012/august/06/third-of-medicaid-doctors-say-no-new-patients.aspx

[10] The PPACA requirement that primary care physician rates match Medicare rates will expire after 2014.

[11] “Least Surprising Health Research Result Ever: Medicaid Increases ER Use,” NCPA, http://healthblog.ncpa.org/least-surprising-health-research-result-ever-medicaid-increases-er-use/

[12] “Medicaid expansion: We already know how the story ends,” Foundation for Government Accountability, http://www.floridafga.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-Medicaid-Expansion-We-already-know-how-the-story-ends.pdf; “Analysis of hospital cost shift in Arizona,” Arizona Chamber Foundation / Lewin Group, http://www.azchamber.com/assets/files/Lewin%20Group.pdf; “Massachusetts health care cost trends: Efficiency of emergency department utilization in Massachusetts,” Massachusetts Health and Human Services, http://www.mass.gov/chia/docs/cost-trend-docs/cost-trends-docs-2012/emergency-department-utilization.pdf

[13] “Oregon Study: Medicaid ‘Had No Significant Effect’ On Health Outcomes vs. Being Uninsured,” Forbes magazine, http://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2013/05/02/oregon-study-medicaid-had-no-significant-effect-on-health-outcomes-vs-being-uninsured/

[14] U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html

[15] “Medicaid and Displacement of Private Insurance,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, http://www.mackinac.org/18788

[16] “Medicaid expansion: We already know how the story ends,” Foundation for Government Accountability, http://www.floridafga.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-Medicaid-Expansion-We-already-know-how-the-story-ends.pdf

[17] “State Progress Toward Health Reform Implementation: Slower Moving States Have Much to Gain,” Urban Institute, Table 2, Page 7, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412485-state-progress-report.pdf; The average cost of uncompensated care per uninsured person nationally was just over $1,000 in 2008, “Covering the Uninsured in 2008: Key Facts about Current Costs, Sources of Payment, and Incremental Costs,” page four, http://kff.org/uninsured/report/covering-the-uninsured-in-2008-key-facts/

The federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) expanded Medicaid to all individuals under age 65 with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). The U.S. Supreme Court ruled, however, that states are not mandated to expand Medicaid coverage. As of January 2014, Georgia and 23 other states had chosen not to expand Medicaid.

Although most reports have indicated 650,000 uninsured individuals are impacted by Georgia’s Medicaid expansion decision, approximately 240,000 have incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the FPL and will be eligible for subsidies in the exchange. That leaves about 410,000 who have incomes below the poverty level but are not currently eligible for Medicaid or other subsidies.[1] So by refusing to expand Medicaid, more than 200,000 uninsured Georgians will receive heavily subsidized, much better quality private insurance.

The focus then becomes the remaining group of 410,000 comprised of able-bodied adults with incomes below 100 percent of FPL. The real debate should revolve around how best to ensure access to health care for these individuals.

The challenges of expanding Medicaid eligibility include uncertainty regarding funding and costs, questions regarding the effectiveness of the Medicaid program and the impact on existing Medicaid recipients.[2]

Uncertainty of federal funding

The federal government has promised to pick up 100 percent of the cost of these newly eligible Medicaid recipients for the first three years, eventually declining to 90 percent. This compares to a 65 percent match for Georgia’s existing Medicaid population. The total cost of expansion is more than $2 billion a year, which is not a trivial amount. As Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute puts it, “Ten percent of a really big number is still a really big number.”[3]

Recent evidence indicates promises of federal funding should be viewed skeptically. President Obama’s 2013 budget proposed shifting more than $50 billion of Medicaid costs onto states,[4] and federal reductions in Medicaid consistently come up in budget talks.[5] From a political perspective, entitlements are extremely hard to scale back once they are expanded. There is also nothing to prevent the federal government from imposing “maintenance of effort” requirements, as they have in the past, to prevent states from reducing eligibility.

The chart below shows the unsustainability of federal health care spending. The Congressional Budget Office projects health care spending to increase dramatically while non-health care spending stays relatively constant and revenues (dotted line) revert to their long-term average of 18 percent of GDP.

Spending by Category in CBO’s Alternative Fiscal Scenario (Percent of GDP)

Perverse incentives

Even if the federal government maintains the promised matching rate of 90 percent, the difference in matching rates creates perverse incentives: Reducing eligibility for able-bodied adults creates $1 of state savings for every 10 recipients who lose benefits, while reducing eligibility for low-income mothers creates $1 of savings for every three individuals who lose benefits. This puts budget writers in a very difficult position during the inevitable next recession.

Uncertainly regarding enrollment of individuals already eligible for Medicaid

Even if Georgia declines to expand Medicaid, the cost of implementing PPACA is projected to increase state costs by more than $100 million. If a large number of currently Medicaid-eligible individuals sign up, that could add another $115 million to annual costs. It would be wise to determine the source of this funding and the effect on Georgia taxpayers before making a decision to expand Medicaid rolls.

The higher federal match rate only applies to newly eligible enrollees in Medicaid; Georgia will continue to pay roughly one-third of the cost of every currently eligible enrollee that signs up. The Urban Institute estimates there are 159,000 adult, low-income Georgians who are currently eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled.[6] The Georgia Department of Community Health assumes fewer than 25,000 (a little over 15 percent) of these Georgians will sign up for Medicaid; this is referred to as the “woodwork effect.” But what if they are wrong? Millions of dollars are being spent around the nation to encourage individuals to sign up for health insurance. If the signup rate is closer to 75 percent, that is more than 119,000 new enrollees and additional annual state costs. In addition, the state estimates only about one-third of the 176,000 children who are currently eligible for Medicaid will enroll, which could also be a low estimate.[7]

Medicaid is already crowding out other state priorities

Initially, the federal government would bear all of the costs, but some Medicaid expansion costs would ultimately fall to the state. As in other states, the Medicaid program is consuming an inordinate share of the state’s revenue, diverting money from other important state priorities such as public safety, education, and infrastructure maintenance and improvements. As the chart below shows, Medicaid now takes one of every five state dollars and its share of the budget has almost doubled over the last decade. Georgia is struggling to fund current Medicaid recipients. A provider fee increase was required last year to raise $689 million to fill a Medicaid funding shortfall.[8]

| $ Growth | Share of Budget | Change in Share of Budget | |

| PK-12 Education | 27% | 40.4% | 0.8% |

| University System | 4% | 9.2% | -1.8% |

| Technical College System | 14% | 1.7% | -0.2% |

| Health Care | 103% | 20.5% | 7.9% |

| Debt Service | 2% | 4.8% | -1.1% |

| Everything Else | 1% | 23.5% | -5.7% |

Negative impact on access for existing vulnerable populations

A third of Georgia doctors already refuse new Medicaid patients.[9] Adding several hundred thousand more recipients to the program will further strain the system and could negatively impact existing Medicaid recipients: the elderly, the disabled, pregnant women and children.[10]

Increased emergency room use

Excessive use of expensive emergency room care is one reason often cited for the need for Medicaid expansion. But an extensive study in Oregon showed Medicaid recipients utilized the emergency room 40 percent more than the uninsured.[11] A majority of the visits were for non-emergency care. This aligns with other studies showing charity care costs actually increased in states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility such as Maine, Arizona and Massachusetts.[12]

Very little, if any, improvement in health status

The Oregon study showed no statistically significant improvement in physical health outcomes for Medicaid recipients versus the uninsured. The study showed better diagnosis and treatment for depression, but Forbes’ Avik Roy notes that this could be accomplished at a fraction of the cost of Medicaid coverage.[13]

Crowd out. As much as a third of the newly insured could be individuals who already have private insurance. According to the Census Bureau,[14] 222,000 Georgia adults under age 65 with income below 100 percent of the FPL are currently covered by private insurance. Even if their policies are not cancelled by ObamaCare regulations, these individuals (or their employers) would be tempted to drop their private insurance in favor of “free” Medicaid coverage.[15] That is one reason why the uninsured rate did not decline in many states that have expanded Medicaid.[16]

Cost effectiveness. By one estimate, the uninsured in Georgia create unpaid bills equal to $2.8 billion, or an average cost of $1,500 per uninsured person, much of it covered by taxpayers.[17] The Georgia Department of Community Health estimates new Medicaid enrollees would cost more than $5,800 per person. If the results of the Oregon study are accurate, Medicaid expansion would nearly quadruple government spending, produce scant improvement in their health outcomes and increase emergency room usage.

Doing nothing is unacceptable, but Georgia can certainly develop a better plan. Georgia is projected to lose $77 million of federal funding for safety net hospitals between 2015 and 2017. The cuts were originally scheduled to begin in 2014, but were delayed for one year. This gives us a window of opportunity to propose a better solution. An upcoming study will examine the alternatives.

[1] A new report from the Kaiser Family Foundation points out that 409,350 Georgians will fall into the “coverage gap” if the state refuses to expand Medicaid (Table 2 in the report, http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/). Large federal subsidies will be available to assist families with incomes above the Federal Poverty Level purchase private insurance, which means that the number left uninsured if Georgia does not expand Medicaid is 409,350 instead of the 650,000 that most news organizations have reported.

[2] “Expanding Medicaid: The Conflicting Incentives Facing States,” Mercatus Institute at George Mason University, http://mercatus.org/expert_commentary/expanding-medicaid-conflicting-incentives-facing-states

[3] “Tanner: No miracle in Medicaid expansion,” by Michael Tanner, Virginian Pilot, http://hamptonroads.com/2014/02/tanner-no-miracle-medicaid-expansion

[4] “Fiscal year 2013: Cuts, consolidations and savings,” Office of Management and Budget, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2013/assets/ccs.pdf

[5] “Proposal to establish federal Medicaid “blended rate” would shift significant costs to states,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, http://www.cbpp.org/files/6-24-11health.pdf

[6] “Opting Out of the Medicaid Expansion under the ACA:

How Many Uninsured Adults Would not Be Eligible for Medicaid?” Urban Institute, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412607-Opting-Out-of-the-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA.pdf

[7] “Medicaid/CHIP Participation Among Children and Parents,” Urban Institute, p. 6, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412719-Medicaid-CHIP-Participation-Among-Children-and-Parents.pdf

[8] http://gov.georgia.gov/press-releases/2013-02-13/deal-signs-provider-fee-bill-ensures-hospitals-critical-medicaid-funding

[9] “Study: Nearly A Third Of Doctors Won’t See New Medicaid Patients,” Kaiser Health News, http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2012/august/06/third-of-medicaid-doctors-say-no-new-patients.aspx

[10] The PPACA requirement that primary care physician rates match Medicare rates will expire after 2014.

[11] “Least Surprising Health Research Result Ever: Medicaid Increases ER Use,” NCPA, http://healthblog.ncpa.org/least-surprising-health-research-result-ever-medicaid-increases-er-use/

[12] “Medicaid expansion: We already know how the story ends,” Foundation for Government Accountability, http://www.floridafga.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-Medicaid-Expansion-We-already-know-how-the-story-ends.pdf; “Analysis of hospital cost shift in Arizona,” Arizona Chamber Foundation / Lewin Group, http://www.azchamber.com/assets/files/Lewin%20Group.pdf; “Massachusetts health care cost trends: Efficiency of emergency department utilization in Massachusetts,” Massachusetts Health and Human Services, http://www.mass.gov/chia/docs/cost-trend-docs/cost-trends-docs-2012/emergency-department-utilization.pdf

[13] “Oregon Study: Medicaid ‘Had No Significant Effect’ On Health Outcomes vs. Being Uninsured,” Forbes magazine, http://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2013/05/02/oregon-study-medicaid-had-no-significant-effect-on-health-outcomes-vs-being-uninsured/

[14] U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html

[15] “Medicaid and Displacement of Private Insurance,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, http://www.mackinac.org/18788

[16] “Medicaid expansion: We already know how the story ends,” Foundation for Government Accountability, http://www.floridafga.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-Medicaid-Expansion-We-already-know-how-the-story-ends.pdf

[17] “State Progress Toward Health Reform Implementation: Slower Moving States Have Much to Gain,” Urban Institute, Table 2, Page 7, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412485-state-progress-report.pdf; The average cost of uncompensated care per uninsured person nationally was just over $1,000 in 2008, “Covering the Uninsured in 2008: Key Facts about Current Costs, Sources of Payment, and Incremental Costs,” page four, http://kff.org/uninsured/report/covering-the-uninsured-in-2008-key-facts/