Last fall, headlines blared the deadly conflagration in the West that scorched hundreds of thousands of acres and tens of thousands of homes. And, of course, many blamed climate change for what was seen as an increasing trend.

By Harold Brown

Last fall, headlines blared the deadly conflagration in the West that scorched hundreds of thousands of acres and tens of thousands of homes. And, of course, many blamed climate change for what was seen as an increasing trend.

Modern perceptions of fire trends often forget the past. A 2017 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences claimed “The United States has experienced some of the largest wildfire years this decade, with over 36,000 km2 (8.9 million acres) burned in 2006, 2007, 2012 and 2015.”

A book published by the Forest History Society in 2011, however, concludes, “The area burned by wildfire each year has decreased by 80–90 percent since the 1930s.” It continues: “However, in recent years, the area burned by wildfire has increased, particularly in the western U.S.”

Wildfires are certainly dangerous, and the danger is directly proportional to the amount and distribution of fuel available for burning. Of course, other factors influence the frequency and intensity of that danger – drought, heat, wind, and proximity of humans, dwellings and property.

In the early 20th century, pine forests of the South were burned regularly to improve growth of wild grasses for cattle grazing. Those may have been counted as forest fires by the U.S. Forest Service, but they were hardly “wildfires,” because most were carefully controlled by landowners. And they most likely prevented serious wildfires by keeping the levels of flammable materials low. It is a longstanding conundrum that preventing forest fires increases the amount of fuel, which increases the severity of subsequent wildfires.

In recent decades, much of the fuel for wildfires is a product of social attitudes and government policies about fire in forests. “Smokey Bear,” promoted by the U.S. Forest Service since the 1940s, probably did more than any other development to reduce the setting of forest fires. The annual number of acres burned decreased from 39 million in the 1930s to 8.5 million in the 1950s, about the same level as today.

But decades of Smokey Bear publicity and caution allowed excess accumulation of combustible fuel in many landscapes. That was compounded by other elements against preventive burning (now called prescribed fire). One was the alarm about air pollution beginning in the 1960s.

A 1972 publication by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on prescribed burning observed that, “the present crusade to abate air pollution levels an accusing finger at all burning.” That accusing finger has also been pointed by fire-fearful inhabitants of subdivisions placed over the last several decades in ever more remote, wooded areas.

Smokey Bear was also advocating against some of his forest mates that evolved and thrive in frequently burned open forests. Two of Georgia’s most prized game birds, bobwhite quail and wild turkey, are more plentiful in pine forests subjected to occasional fire.

A 1972 Atlant Constitution article reported the Forest Service was beginning a policy of “prescribed burning.” It noted, “A half-century of official fire suppression has allowed the build-up of fuel – dead trees, fallen limbs, leaves and the like – so that when fire does occur it burns hotter and is harder to put out.”

It took decades for states to partially accept prescribed fire as useful rather than harmful. In a 2012 scientific article, the California authors observed: “It is almost an axiom in California forest management that given many existing restrictions, prescribed and managed wildfires will never be practical on a large scale for fuels reduction treatments.”

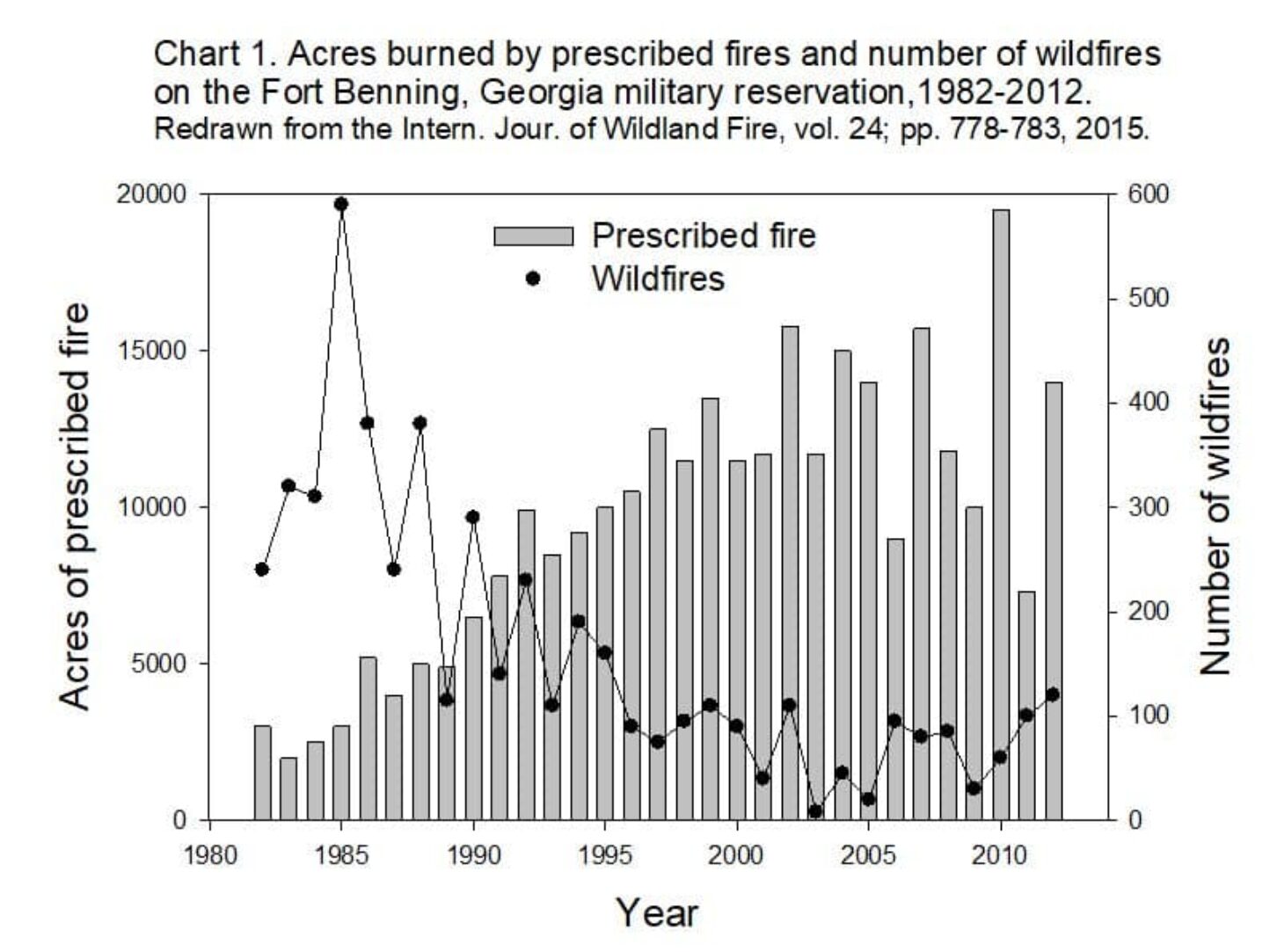

One example of the preventive nature of prescribed burning is on the 180,000-acre Fort Benning military base near Columbus, Ga. Over 30 years, an increase of area burned was accompanied by a dramatic drop in wildfires (see chart 1).

One example of the preventive nature of prescribed burning is on the 180,000-acre Fort Benning military base near Columbus, Ga. Over 30 years, an increase of area burned was accompanied by a dramatic drop in wildfires (see chart 1).

A comparison of the Southeast (11 states) with the far West (11 states, not including Hawaii or Alaska) shows the contrasting approach to wildfire. The annual number of wildfires is similar since 2002, but the area burned is more than sevenfold larger in the West.

The Southeast uses much more prescribed burning – nearly eight times as many fires – burning 3.7 times more acres.

The problem of wildfire damage in the western United States is a complicated issue, but it is clear that reducing the amount of combustible material in its wildlands will help limit future damage. Blaming climate change for the increasing acreage of wildfire damage in California is no more logical than crediting it for decreases in South Carolina (see chart 2).

Harold Brown is professor emeritus at the University of Georgia and a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. The Foundation is an independent, nonprofit think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (April 26, 2019). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.

By Harold Brown

Harold Brown

Last fall, headlines blared the deadly conflagration in the West that scorched hundreds of thousands of acres and tens of thousands of homes. And, of course, many blamed climate change for what was seen as an increasing trend.

Modern perceptions of fire trends often forget the past. A 2017 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences claimed “The United States has experienced some of the largest wildfire years this decade, with over 36,000 km2 (8.9 million acres) burned in 2006, 2007, 2012 and 2015.”

A book published by the Forest History Society in 2011, however, concludes, “The area burned by wildfire each year has decreased by 80–90 percent since the 1930s.” It continues: “However, in recent years, the area burned by wildfire has increased, particularly in the western U.S.”

Wildfires are certainly dangerous, and the danger is directly proportional to the amount and distribution of fuel available for burning. Of course, other factors influence the frequency and intensity of that danger – drought, heat, wind, and proximity of humans, dwellings and property.

In the early 20th century, pine forests of the South were burned regularly to improve growth of wild grasses for cattle grazing. Those may have been counted as forest fires by the U.S. Forest Service, but they were hardly “wildfires,” because most were carefully controlled by landowners. And they most likely prevented serious wildfires by keeping the levels of flammable materials low. It is a longstanding conundrum that preventing forest fires increases the amount of fuel, which increases the severity of subsequent wildfires.

In recent decades, much of the fuel for wildfires is a product of social attitudes and government policies about fire in forests. “Smokey Bear,” promoted by the U.S. Forest Service since the 1940s, probably did more than any other development to reduce the setting of forest fires. The annual number of acres burned decreased from 39 million in the 1930s to 8.5 million in the 1950s, about the same level as today.

But decades of Smokey Bear publicity and caution allowed excess accumulation of combustible fuel in many landscapes. That was compounded by other elements against preventive burning (now called prescribed fire). One was the alarm about air pollution beginning in the 1960s.

A 1972 publication by the U.S. Department of Agriculture on prescribed burning observed that, “the present crusade to abate air pollution levels an accusing finger at all burning.” That accusing finger has also been pointed by fire-fearful inhabitants of subdivisions placed over the last several decades in ever more remote, wooded areas.

Smokey Bear was also advocating against some of his forest mates that evolved and thrive in frequently burned open forests. Two of Georgia’s most prized game birds, bobwhite quail and wild turkey, are more plentiful in pine forests subjected to occasional fire.

A 1972 Atlant Constitution article reported the Forest Service was beginning a policy of “prescribed burning.” It noted, “A half-century of official fire suppression has allowed the build-up of fuel – dead trees, fallen limbs, leaves and the like – so that when fire does occur it burns hotter and is harder to put out.”

It took decades for states to partially accept prescribed fire as useful rather than harmful. In a 2012 scientific article, the California authors observed: “It is almost an axiom in California forest management that given many existing restrictions, prescribed and managed wildfires will never be practical on a large scale for fuels reduction treatments.”

One example of the preventive nature of prescribed burning is on the 180,000-acre Fort Benning military base near Columbus, Ga. Over 30 years, an increase of area burned was accompanied by a dramatic drop in wildfires (see chart 1).

One example of the preventive nature of prescribed burning is on the 180,000-acre Fort Benning military base near Columbus, Ga. Over 30 years, an increase of area burned was accompanied by a dramatic drop in wildfires (see chart 1).

A comparison of the Southeast (11 states) with the far West (11 states, not including Hawaii or Alaska) shows the contrasting approach to wildfire. The annual number of wildfires is similar since 2002, but the area burned is more than sevenfold larger in the West.

The Southeast uses much more prescribed burning – nearly eight times as many fires – burning 3.7 times more acres.

The problem of wildfire damage in the western United States is a complicated issue, but it is clear that reducing the amount of combustible material in its wildlands will help limit future damage. Blaming climate change for the increasing acreage of wildfire damage in California is no more logical than crediting it for decreases in South Carolina (see chart 2).

Harold Brown is professor emeritus at the University of Georgia and a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. The Foundation is an independent, nonprofit think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (April 26, 2019). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.