It’s time to redouble reform efforts in civil asset forfeiture.

By Benita M. Dodd

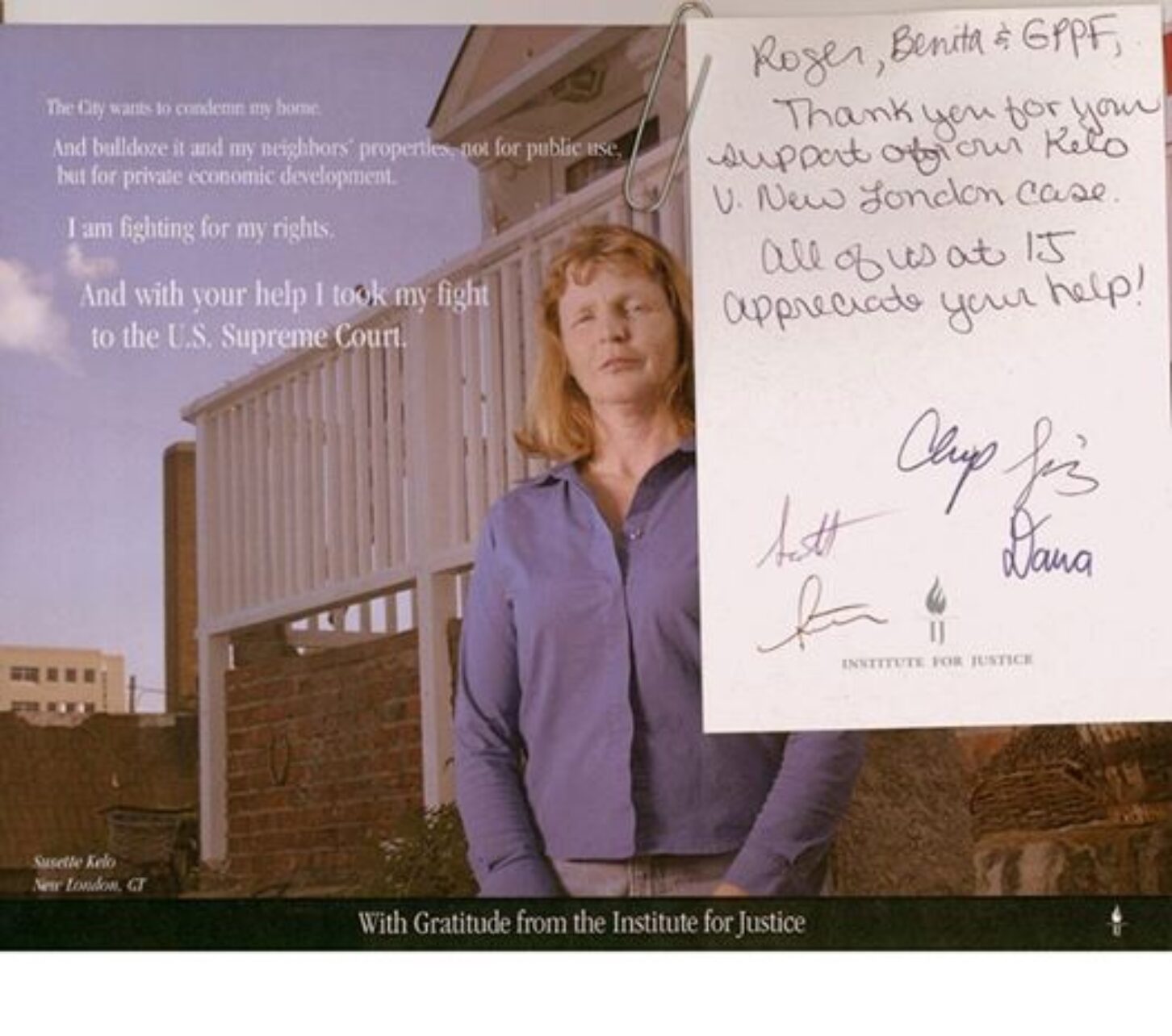

Susette Kelo was minding her own business when the city of New London, Conn., set its sights on her home. The city wanted to take the property and demolish the home, along with her neighbors’ homes, to make way for private economic development.

Kelo decided to fight back. The Institute for Justice led her fight, joined by think tanks around the country, including the Georgia Public Policy Foundation.

Remember the shocked property owners around the nation when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on June 10, 2005, that the city could take Kelo’s home and land against her will?

The Court said it was the states’ responsibility to toughen the laws on eminent domain that enabled governments to abuse the rights of private property owners.

Today, 10 years after the Court ruling, Kelo’s property stands vacant. The private development failed spectacularly. Kelo’s battle was lost but the war was won: Outrage over the ruling led the states to work toward more protections for property owners and legislation against abuse of eminent domain by governments. A movie about her battle, “Little Pink House,” begins filming in September. And Georgia took the High Court at its word: The state implemented one of the nation’s toughest eminent domain laws in the nation.

Yet government continues abusing its citizens’ property rights.

“Alex,” too, was minding his own business when his older sister borrowed his car for a weekend trip with friends out of state. She was stopped for speeding in North Carolina; police found two marijuana joints and seized his car.

“You can come get it,” he was told. The high school student, who’d scrimped and saved the $700 to buy the car, couldn’t afford to take time off his summer job and pay for the travel and impound charges.

“I rode my bicycle in the heat to and from my job for the rest of the summer.”

All grown up and an executive in Atlanta now, he still looks wistfully back on that first car he owned. He never saw it again; it was a long time before he could afford another.

Alex’s tale of loss is repeated far too often across the nation and in Georgia. The ability of government to arbitrarily seize the private property of Americans – without a conviction, let alone filing criminal charges – is one of the most egregious holes in the American legal system and a flagrant abuse of private property rights on par with Kelo v. New London.

Innocuously called “civil asset forfeiture,” the process began with noble intentions. Now it’s a cash cow for too many agencies and the bane of too many innocent victims unable to fight back against the long arm of the law. Law authorities stubbornly resist reform, even in Georgia; they get a cut in the proceeds from what they seize. Only five states prohibit such seizure: Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico and North Carolina.

The Institute for Justice calls it “policing for profit.” In a new publication endorsed by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and more than a dozen other groups, the Heritage Foundation calls it, “Arresting Your Property.” Read the publication and a litany of abuses here.

In a legal memorandum for the Heritage Foundation, John G. Malcolm, a former board member of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and senior legal fellow at Heritage, explains: “Civil asset forfeiture is based on a fiction: that property can be guilty of a crime and thereby forfeited to the sovereign regardless of whether any individual is ever charged with or convicted of a crime related to that property.”

How many low-income Americans can’t afford to retrieve grandma’s furniture seized because a grandson was surreptitiously dealing pot stashed in his bedroom? How many struggling single parents lose the only household car because of a child’s drug possession? How many entrepreneurs and students lose money because an officer decides they have a “suspicious” amount of money in their possession during a “routine” traffic stop?

The answer, as “Arresting Your Property” recounts, is too many. The Institute for Justice, “the national law firm for liberty,” has once again taken the lead, joined by an unusual coalition of national organizations: Heritage, the American Civil Liberties Union, American Center for Law and Justice, American Legislative Exchange Council and the Charles Koch Institute, among others.

The Georgia Public Policy Foundation is among the state liberty groups championing reforms that protect all innocent citizens, including those who can’t afford to take on government. Among those reforms: fairness, transparency, accountability and prohibiting law enforcement agencies from profiting directly from proceeds. We toughened eminent domain laws. Now, policymakers need to quit rearranging the deck chairs and scuttle the private property shipwreck that civil asset forfeiture represents today.

Benita M. Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation.

By Benita M. Dodd

Susette Kelo was minding her own business when the city of New London, Conn., set its sights on her home. The city wanted to take the property and demolish the home, along with her neighbors’ homes, to make way for private economic development.

Kelo decided to fight back. The Institute for Justice led her fight, joined by think tanks around the country, including the Georgia Public Policy Foundation.

Remember the shocked property owners around the nation when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on June 10, 2005, that the city could take Kelo’s home and land against her will?

The Court said it was the states’ responsibility to toughen the laws on eminent domain that enabled governments to abuse the rights of private property owners.

Today, 10 years after the Court ruling, Kelo’s property stands vacant. The private development failed spectacularly. Kelo’s battle was lost but the war was won: Outrage over the ruling led the states to work toward more protections for property owners and legislation against abuse of eminent domain by governments. A movie about her battle, “Little Pink House,” begins filming in September. And Georgia took the High Court at its word: The state implemented one of the nation’s toughest eminent domain laws in the nation.

Yet government continues abusing its citizens’ property rights.

“Alex,” too, was minding his own business when his older sister borrowed his car for a weekend trip with friends out of state. She was stopped for speeding in North Carolina; police found two marijuana joints and seized his car.

“You can come get it,” he was told. The high school student, who’d scrimped and saved the $700 to buy the car, couldn’t afford to take time off his summer job and pay for the travel and impound charges.

“I rode my bicycle in the heat to and from my job for the rest of the summer.”

All grown up and an executive in Atlanta now, he still looks wistfully back on that first car he owned. He never saw it again; it was a long time before he could afford another.

Alex’s tale of loss is repeated far too often across the nation and in Georgia. The ability of government to arbitrarily seize the private property of Americans – without a conviction, let alone filing criminal charges – is one of the most egregious holes in the American legal system and a flagrant abuse of private property rights on par with Kelo v. New London.

Innocuously called “civil asset forfeiture,” the process began with noble intentions. Now it’s a cash cow for too many agencies and the bane of too many innocent victims unable to fight back against the long arm of the law. Law authorities stubbornly resist reform, even in Georgia; they get a cut in the proceeds from what they seize. Only five states prohibit such seizure: Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico and North Carolina.

The Institute for Justice calls it “policing for profit.” In a new publication endorsed by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and more than a dozen other groups, the Heritage Foundation calls it, “Arresting Your Property.” Read the publication and a litany of abuses here.

In a legal memorandum for the Heritage Foundation, John G. Malcolm, a former board member of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and senior legal fellow at Heritage, explains: “Civil asset forfeiture is based on a fiction: that property can be guilty of a crime and thereby forfeited to the sovereign regardless of whether any individual is ever charged with or convicted of a crime related to that property.”

How many low-income Americans can’t afford to retrieve grandma’s furniture seized because a grandson was surreptitiously dealing pot stashed in his bedroom? How many struggling single parents lose the only household car because of a child’s drug possession? How many entrepreneurs and students lose money because an officer decides they have a “suspicious” amount of money in their possession during a “routine” traffic stop?

The answer, as “Arresting Your Property” recounts, is too many. The Institute for Justice, “the national law firm for liberty,” has once again taken the lead, joined by an unusual coalition of national organizations: Heritage, the American Civil Liberties Union, American Center for Law and Justice, American Legislative Exchange Council and the Charles Koch Institute, among others.

The Georgia Public Policy Foundation is among the state liberty groups championing reforms that protect all innocent citizens, including those who can’t afford to take on government. Among those reforms: fairness, transparency, accountability and prohibiting law enforcement agencies from profiting directly from proceeds. We toughened eminent domain laws. Now, policymakers need to quit rearranging the deck chairs and scuttle the private property shipwreck that civil asset forfeiture represents today.