Health Policy News and Views

Compiled by Benita M. Dodd

(This Labor Day week, the reference to the CBO quote about the Affordable Care Act is the extent of the “Health Policy News and Views!”)

Around Labor Day weekend, the squeaky wheels turn to the issues of equal pay for equal work and raising the minimum wage to a “fair” wage. And yet, how do you count equal work? And who decides what is an acceptable “fair” wage?

A long time and another career ago, I was notified of my annual pay raise after receiving a glowing performance review. My supervisor raved about my hard work, talent and ingenuity. So when I saw what the raise was destined to be, I raised Cain with my supervisor.

“I deserve a better raise than this,” I complained. “I work harder than most of the people working for you.”

He was a great supervisor, and he agreed with me. So much that he went to speak to the department manager about it.

Soon, I was called into my department manager’s office.

“I’m sorry,” he explained, “but if we give YOU a bigger pay raise, we have to take it from someone else in the department. And that wouldn’t be fair.”

I do believe that’s when I first felt the stirrings of conservatism in my soul.

Why should I be paid less because it wouldn’t be “fair” to reduce someone else’s pay raise?

I’m all about all for one and one for all when it comes to the Three Musketeers, and I’m all about equal pay for equal work. But, as unions show all the time in their protectionist contracts, lousy workers and excellent workers may have equal positions and equal pay but they don’t perform equal work. Second, let me just point out: This male-female pay gap is not all it’s claimed to be; this, however, is not what my gripe was about.

I wasn’t doing equal work. I was doing BETTER work than the guys. It irked me that there was no way for me to surge ahead, even with a higher, better work ethic.

So it is with that “fair” wage. Most people who start at the minimum wage soon move beyond that. If you force an employer to raise the wage for everyone, there are fewer entry level positions available, less opportunity for an employer to expand his workforce or his business, and less ability for employers to reward the best workers and incentivize upward mobility.

It reminds me of a comic strip I saw recently, in which the boss tells his employee, “I’d like to pay you what you’re worth, but minimum wage laws won’t allow me to.”

Now I work for a non-profit education organization, where I still don’t earn what I’m worth (in my inflated opinion), but that is by choice. And I know that it’s not because someone else is getting it in my stead. I’m proud to be at the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, which encourages upward mobility through individual responsibility.

This Labor Day, I recalled my father’s hard work as a carpenter by trade and my mother working as a nurse. I remembered my father’s family, humble fisher folk off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa. I remember finding a photograph of my great grandmother, smiling proudly, dressed in her spotless maid’s uniform.

I remember how my father had to leave his hometown and relatives to ply his trade on the other side of the country in order to support his wife and children during the apartheid era of discrimination in jobs, housing, education … discriminatory everything. I remember that my parents couldn’t afford to send me to university — they couldn’t even afford to buy a house! — and I was fortunate enough to earn a scholarship.

I remember being the first in my family to graduate from university. I remember leaving apartheid South Africa because I wanted my children to have a safer, better life without discrimination and opportunities based on how hard they work.

And America gave that to us. But there’s now.

I remember working on the Foundation’s Friday Facts for this past Labor Day weekend. And I remember the Quotes of Note that stuck in my craw: One, by Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute, talking about the highest rate ever of welfare beneficiaries in this country. Another, from the Congressional Budget Office, projecting a decline in worker productivity because many Americans won’t want to work more hours and lose their health care premium subsidies under the Affordable Care Act.

Just this afternoon, a worker friend from our office complex stopped by to ask about my Labor Day weekend.

“I’m here,” I responded. “Didn’t win the Lottery. Again.”

“Well, when you do …” and I jokingly finished the sentence for him, “I’ll remember the little people. You’ll get a tidy little settlement.”

“Nah. If you’ll just get me a truck and a toolbox, I’ll take it from there.”

That is America. THAT is what a healthy Labor Day attitude is about. And THAT is what the Georgia Public Policy Foundation is about. Excellence and individual initiative; friends who help each other. Not an expectation that government will do it for us with other people’s hard-earned dollars or, worse, discourage us from working harder.

Thank you for your support. I hope you’ll continue to support us. If you don’t, you should. Contribute here.

Health Policy News and Views

Compiled by Benita M. Dodd

(This Labor Day week, the reference to the CBO quote about the Affordable Care Act is the extent of the “Health Policy News and Views!”)

BENITA DODD

Around Labor Day weekend, the squeaky wheels turn to the issues of equal pay for equal work and raising the minimum wage to a “fair” wage. And yet, how do you count equal work? And who decides what is an acceptable “fair” wage?

A long time and another career ago, I was notified of my annual pay raise after receiving a glowing performance review. My supervisor raved about my hard work, talent and ingenuity. So when I saw what the raise was destined to be, I raised Cain with my supervisor.

“I deserve a better raise than this,” I complained. “I work harder than most of the people working for you.”

He was a great supervisor, and he agreed with me. So much that he went to speak to the department manager about it.

Soon, I was called into my department manager’s office.

“I’m sorry,” he explained, “but if we give YOU a bigger pay raise, we have to take it from someone else in the department. And that wouldn’t be fair.”

I do believe that’s when I first felt the stirrings of conservatism in my soul.

Why should I be paid less because it wouldn’t be “fair” to reduce someone else’s pay raise?

I’m all about all for one and one for all when it comes to the Three Musketeers, and I’m all about equal pay for equal work. But, as unions show all the time in their protectionist contracts, lousy workers and excellent workers may have equal positions and equal pay but they don’t perform equal work. Second, let me just point out: This male-female pay gap is not all it’s claimed to be; this, however, is not what my gripe was about.

I wasn’t doing equal work. I was doing BETTER work than the guys. It irked me that there was no way for me to surge ahead, even with a higher, better work ethic.

So it is with that “fair” wage. Most people who start at the minimum wage soon move beyond that. If you force an employer to raise the wage for everyone, there are fewer entry level positions available, less opportunity for an employer to expand his workforce or his business, and less ability for employers to reward the best workers and incentivize upward mobility.

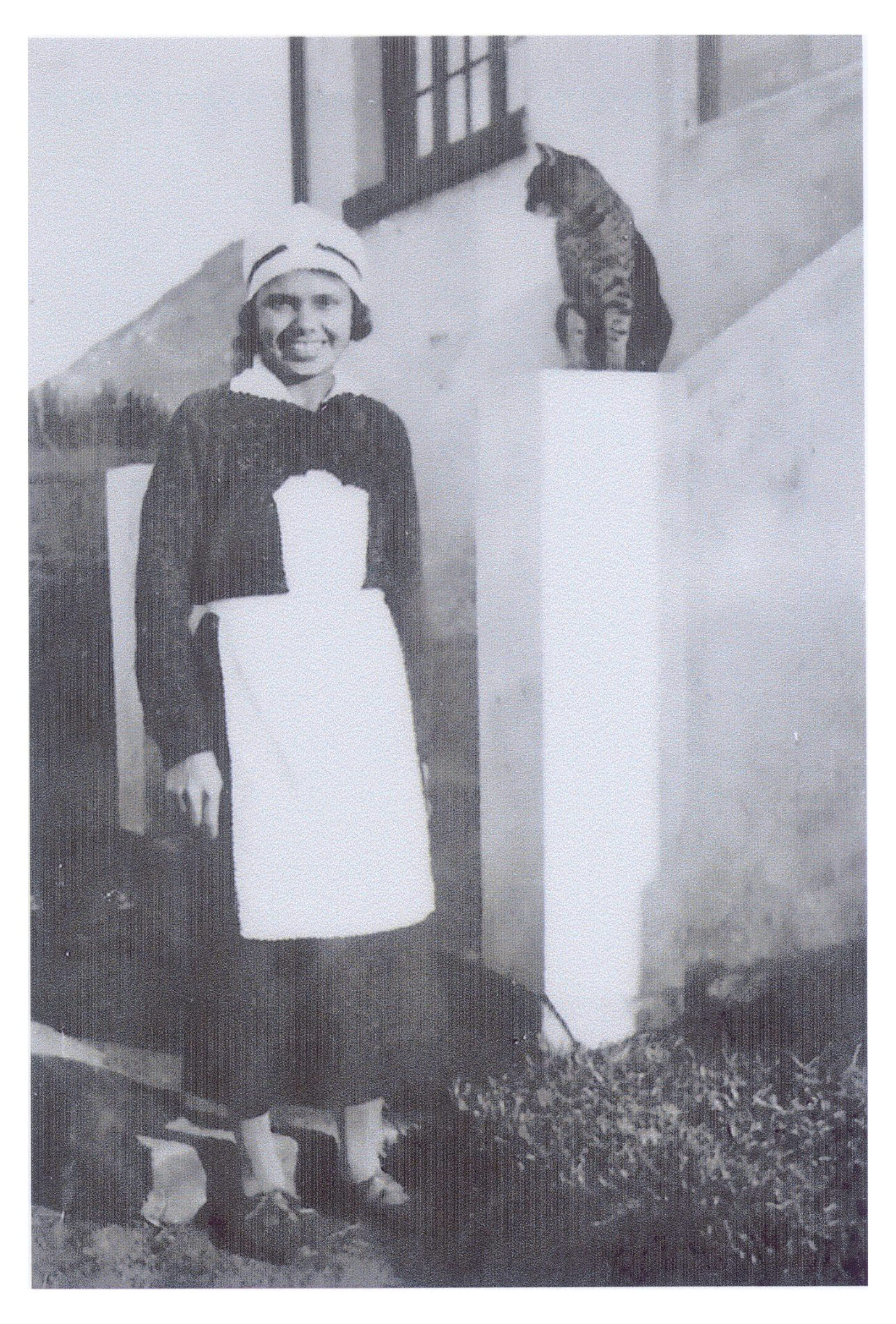

Benita Dodd’s grandmother, a maid in the early 1900s in South Africa.

It reminds me of a comic strip I saw recently, in which the boss tells his employee, “I’d like to pay you what you’re worth, but minimum wage laws won’t allow me to.”

Now I work for a non-profit education organization, where I still don’t earn what I’m worth (in my inflated opinion), but that is by choice. And I know that it’s not because someone else is getting it in my stead. I’m proud to be at the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, which encourages upward mobility through individual responsibility.

This Labor Day, I recalled my father’s hard work as a carpenter by trade and my mother working as a nurse. I remembered my father’s family, humble fisher folk off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa. I remember finding a photograph of my great grandmother, smiling proudly, dressed in her spotless maid’s uniform.

I remember how my father had to leave his hometown and relatives to ply his trade on the other side of the country in order to support his wife and children during the apartheid era of discrimination in jobs, housing, education … discriminatory everything. I remember that my parents couldn’t afford to send me to university — they couldn’t even afford to buy a house! — and I was fortunate enough to earn a scholarship.

I remember being the first in my family to graduate from university. I remember leaving apartheid South Africa because I wanted my children to have a safer, better life without discrimination and opportunities based on how hard they work.

And America gave that to us. But there’s now.

I remember working on the Foundation’s Friday Facts for this past Labor Day weekend. And I remember the Quotes of Note that stuck in my craw: One, by Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute, talking about the highest rate ever of welfare beneficiaries in this country. Another, from the Congressional Budget Office, projecting a decline in worker productivity because many Americans won’t want to work more hours and lose their health care premium subsidies under the Affordable Care Act.

Just this afternoon, a worker friend from our office complex stopped by to ask about my Labor Day weekend.

“I’m here,” I responded. “Didn’t win the Lottery. Again.”

“Well, when you do …” and I jokingly finished the sentence for him, “I’ll remember the little people. You’ll get a tidy little settlement.”

“Nah. If you’ll just get me a truck and a toolbox, I’ll take it from there.”

That is America. THAT is what a healthy Labor Day attitude is about. And THAT is what the Georgia Public Policy Foundation is about. Excellence and individual initiative; friends who help each other. Not an expectation that government will do it for us with other people’s hard-earned dollars or, worse, discourage us from working harder.

Thank you for your support. I hope you’ll continue to support us. If you don’t, you should. Contribute here.