Citing an anticipated 2.9 million more people moving into metro Atlanta by 2050, the Atlanta Regional Commission Board this week approved a $172.6 billion “fiscally constrained” Regional Transportation Plan (RTP).

Fiscally constrained, to the region’s metropolitan planning organization, means “enough revenue to cover the expected spending over the life of the plan.”

Would that there were enough common sense, too, to cover the blueprint, which envisions “a world-class multimodal network designed to support our economy and healthy and livable communities.”

What does Atlanta get for $172.6 billion?

With or without the plan, the ARC admits, the region’s congestion will worsen. It anticipates that with a population of 8.2 million in 2050, a trip taking 31 minutes today would be 35 minutes in 2050 without the projects. Carry out the projects and the trip time shrinks to 33 minutes by 2050.

Perhaps the reason for the lack of progress is in the ARC’s approach to solving the region’s transportation challenges. In its own words, “The most cost efficient and sustainable way to leverage maximum value from our existing infrastructure is to reduce the number and length of trips it serves.”

The region’s workers and commuters might disagree. To “leverage maximum value,” a logical person would argue, would be to improve mobility by facilitating the preferred mode of travel for the vast majority: the automobile.

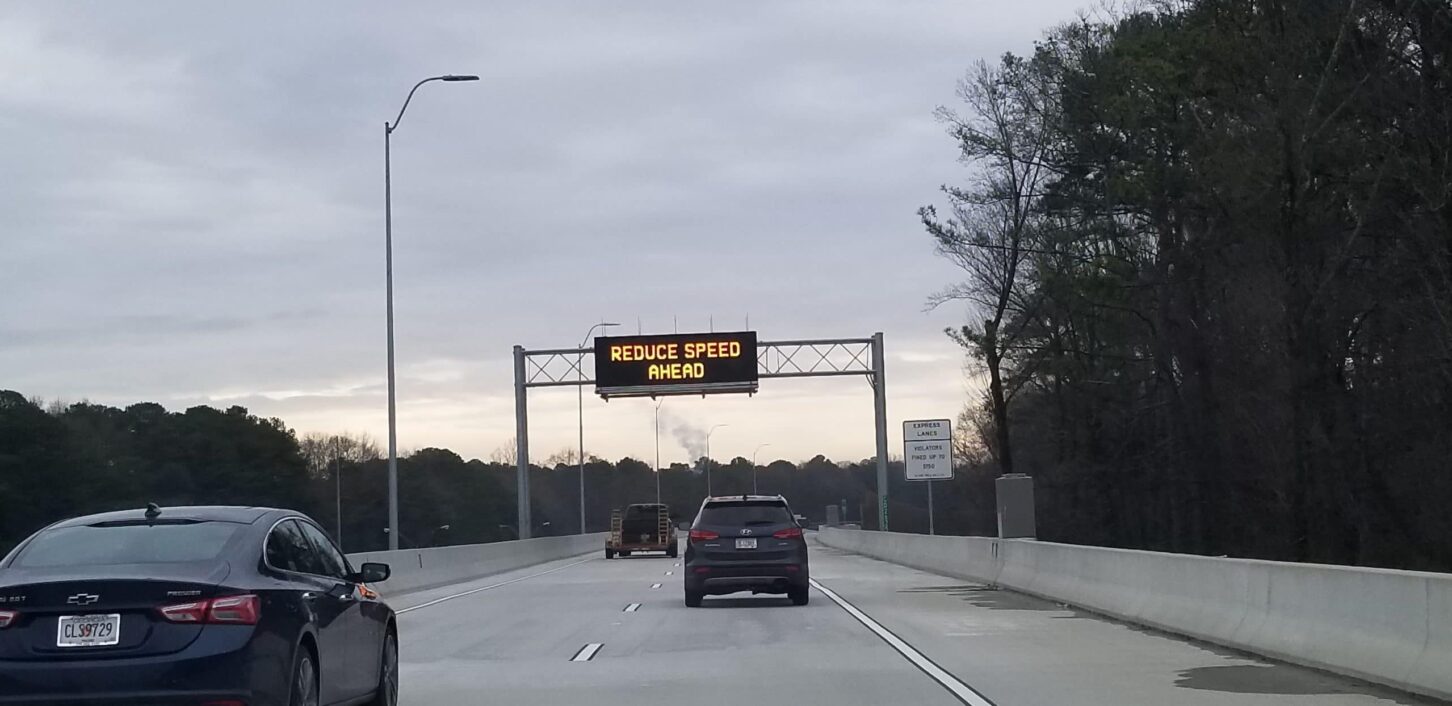

Instead, planners include smart decisions like expanding toll lanes with counterintuitive strategies that exacerbate congestion and hinder mobility.

Among their strategies are road diets, euphemistically called “Complete Streets,” which encourage “walkability” and eliminate car lanes, add bicycle lanes and, overall, hinder passage for motorists. (In one case, the city of Atlanta has shifted an entire auto lane to bicyclists and scooters.) Streetscapes, raised medians and bicycle lanes on busy roads are misplaced priorities when it comes to leveraging maximum value from existing transportation infrastructure.

The ARC blueprint explains:

To ensure all capacity expansion projects accommodate all roadway users, ARC also requires arterial projects be implemented as complete streets. A complete street project ensures that the design of the roadway is context-sensitive. This can include amenities to support transit services, provisions of pedestrian and bicycle facilities, and the provision of safe crossings and intersections.

The plan dedicates $11 billion to transit and another $10 billion to bicycle paths, pedestrian trails and “livable community initiatives.” The plan would more than double transit ridership and promote transit-oriented development. But it’s too late: Transit use is in ongoing decline, in Atlanta and around the nation, even as door-to-door ride-hail services surge. Furthermore, while advocates of transit work toward ridership numbers, the ridership share is declining, too, relative to population growth. Despite this, the plan includes the recurring pipe dream of commuter rail between Lovejoy and East Point and the expansion of the underwhelming Atlanta Streetcar system, along with less costly bus-rapid transit routes.

Way back when, the overt reason for the ARC’s transit push and highway aversion was that the region was failing to meet federal air quality standards. But as the auto fleet updates, efficiencies improve and emissions plummet. The ARC’s performance report admits as much: With or without the blueprint, ozone-causing auto emissions are well below the federal threshold.

Adding insult to injury, along with $172.6 billion, the ARC needs $18 billion more in state and local funds to “staff and operate the various agencies and departments charged with implementing the plan.”

The blueprint’s hat-tip to technological improvements is 140 projects targeting “Road System Optimization and Safety,” ranging from traffic signal synchronization to autonomous vehicles. It also describes the region as “one of the most connected in the country,” as the Georgia Department of Transportation deploys Dedicated Short Range Communications (DSRC), vehicle-to-vehicle communication, to thousands of intersections.

This may be the equivalent of the rabbit ear antenna. A recent article noted DSRC “has been woefully underused by [U.S.] DOT and many car manufacturers have adopted alternative technologies.”

Hope springs eternal, however, and one statement gives hope for a better outcome: that “the RTP is not a fly in amber after adoption, but rather a living document that is gradually adjusted and augmented between quadrennial updates.”