Georgia has seen dramatic increases in public school staffing while the needle has barely moved on student achievement.

By Ben Scafidi

Cuts to family budgets have been significant since the Great Recession began in late 2007. Likewise, cuts to public school budgets in Georgia – and nationally – have been significant as well. That said, the economic challenges facing public schools during the Great Recession need to be put in historical context.

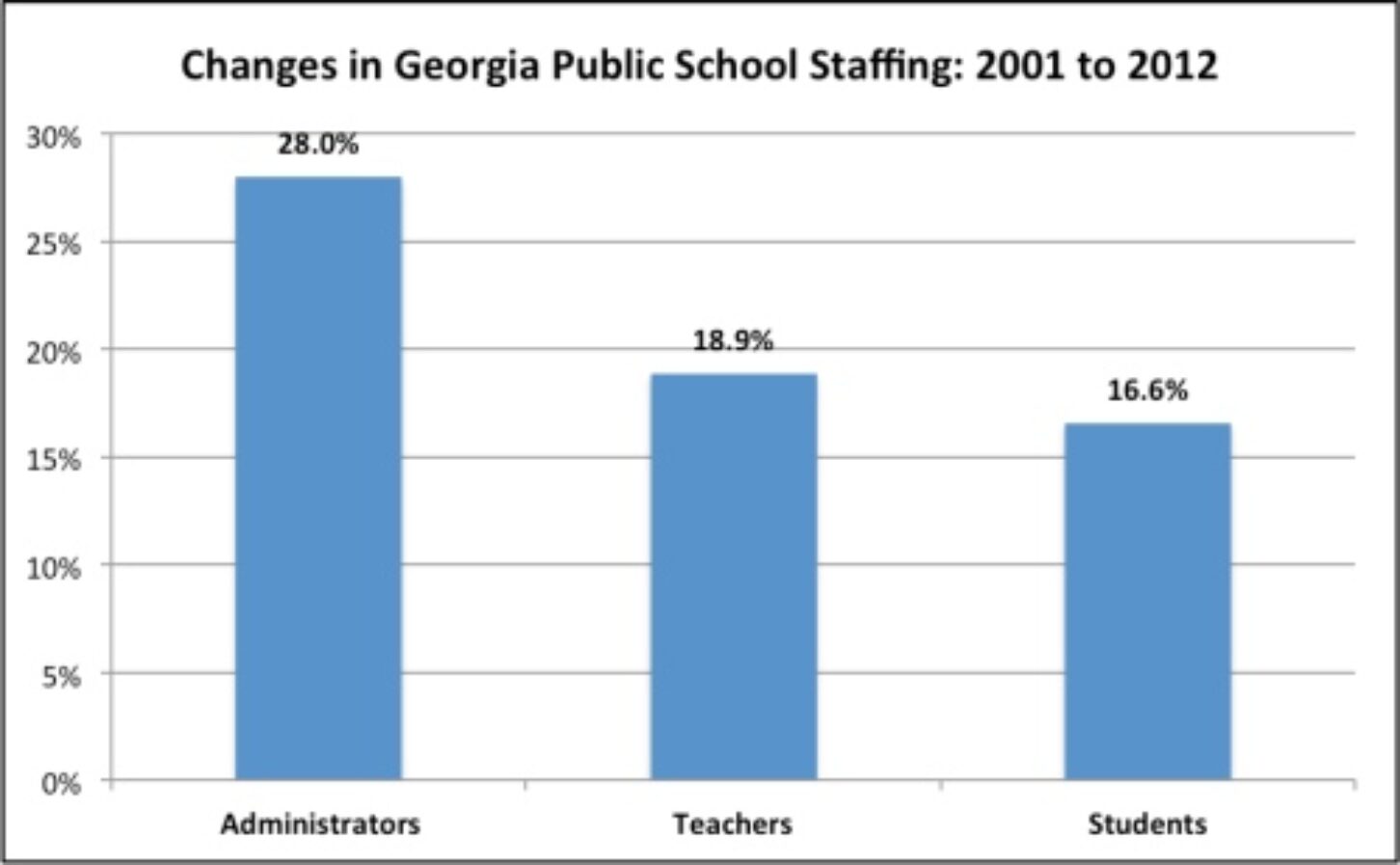

A recent Georgia State University policy brief reported an 18.9 percent increase in the state’s public school teachers between 2001 and 2012, and a 28 percent increase in school-based administrators.

The report did not mention the increase in students during that same period: 16.6 percent. Thus, in 2012 public school students in Georgia had proportionately more staffing than students had in 2001. Put differently, in 2012 Georgia public school students had smaller pupil-teacher ratios and more school administrators to attend to their needs than students in 2001, even factoring in the effects of the Great Recession.

To be clear, Georgia State University’s policy brief excluded from its calculations such public school system workers as “employees assigned to facilities without students,” where “transportation, central office, or maintenance facilities, are a few examples.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics at the U.S. Department of Education, the number of Georgia public school district administrators and district support staff increased by 29 percent between 2001 and 2011 – almost double the increase in students. (The most recent data available are from 2011.)

What is clear is that Georgia public schools have been increasing their employment of teachers at a higher rate than their increase in students. And Georgia public schools have been increasing their employment of school and central office administrators at a much higher rate than their increase in both teachers and students!

Unfortunately, in spite of the these significant increases in public school staffing that have gone on in Georgia and around the nation for decades, it is worth mentioning that public high school graduation rates are about where they were in 1970.

Thus, we have had dramatic increases in public school staffing while the needle has barely moved on student achievement.

In two “staffing surge” reports for the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, I showed the significant opportunity cost – in Georgia and in virtually every other state – of these excessive staffing increases in administration and others who were not lead teachers. For example, between 1992 and 2009, Georgia public schools increased their employment of non-lead teachers by 74 percent even as the number of students increased 41 percent. (The number of lead teachers increased 80 percent during that period – about double the increase in students.)

Had Georgia increased its employment of these administrators and other staff by 41 percent – that is, the same rate as the increase in students, Georgia public schools would have saved almost $1 billion per year in annual recurring savings. (My cautious assumption was that each non-lead teacher’s salary plus benefit costs were $40,000 per employee, which is surely much lower than the truth.)

Imagine what Georgia public schools could do with almost $1 billion per year

- Give each teacher about an $8,000-per-year permanent salary increase

- Give residents a property tax cut

- Offer students scholarships to attend the schools of their parents’ choice

- Do some of all of the above

Georgia public schools had a choice: (a) Disproportionately increase employment of non-lead teachers or (b) Give teachers pay raises, cut property taxes and offer more school choices to parents. They chose the former and reduced the number of school days to boot. Now Governor Deal and the Legislature are set to give our local school boards an additional $550 million per year in funding.

Where will public school boards spend these additional taxpayer funds? Pretend you’re a student and complete the following sentence: Those who cannot remember the past … Put another way: If history is any guide, Georgia’s teachers, parents and taxpayers may not be happy with their answer.

Scafidi’s “staffing surge” research is available at www.edchoice.org/Research/National-Research.

Data broken down by school system is available in PDF or spreadsheet format.

Benjamin Scafidi is a professor of economics at Georgia College and a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. The views expressed here are his own. The Foundation is an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.)

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (February 21, 2014). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.

By Ben Scafidi

Cuts to family budgets have been significant since the Great Recession began in late 2007. Likewise, cuts to public school budgets in Georgia – and nationally – have been significant as well. That said, the economic challenges facing public schools during the Great Recession need to be put in historical context.

A recent Georgia State University policy brief reported an 18.9 percent increase in the state’s public school teachers between 2001 and 2012, and a 28 percent increase in school-based administrators.

The report did not mention the increase in students during that same period: 16.6 percent. Thus, in 2012 public school students in Georgia had proportionately more staffing than students had in 2001. Put differently, in 2012 Georgia public school students had smaller pupil-teacher ratios and more school administrators to attend to their needs than students in 2001, even factoring in the effects of the Great Recession.

To be clear, Georgia State University’s policy brief excluded from its calculations such public school system workers as “employees assigned to facilities without students,” where “transportation, central office, or maintenance facilities, are a few examples.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics at the U.S. Department of Education, the number of Georgia public school district administrators and district support staff increased by 29 percent between 2001 and 2011 – almost double the increase in students. (The most recent data available are from 2011.)

What is clear is that Georgia public schools have been increasing their employment of teachers at a higher rate than their increase in students. And Georgia public schools have been increasing their employment of school and central office administrators at a much higher rate than their increase in both teachers and students!

Unfortunately, in spite of the these significant increases in public school staffing that have gone on in Georgia and around the nation for decades, it is worth mentioning that public high school graduation rates are about where they were in 1970.

Thus, we have had dramatic increases in public school staffing while the needle has barely moved on student achievement.

In two “staffing surge” reports for the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, I showed the significant opportunity cost – in Georgia and in virtually every other state – of these excessive staffing increases in administration and others who were not lead teachers. For example, between 1992 and 2009, Georgia public schools increased their employment of non-lead teachers by 74 percent even as the number of students increased 41 percent. (The number of lead teachers increased 80 percent during that period – about double the increase in students.)

Had Georgia increased its employment of these administrators and other staff by 41 percent – that is, the same rate as the increase in students, Georgia public schools would have saved almost $1 billion per year in annual recurring savings. (My cautious assumption was that each non-lead teacher’s salary plus benefit costs were $40,000 per employee, which is surely much lower than the truth.)

Imagine what Georgia public schools could do with almost $1 billion per year

- Give each teacher about an $8,000-per-year permanent salary increase

- Give residents a property tax cut

- Offer students scholarships to attend the schools of their parents’ choice

- Do some of all of the above

Georgia public schools had a choice: (a) Disproportionately increase employment of non-lead teachers or (b) Give teachers pay raises, cut property taxes and offer more school choices to parents. They chose the former and reduced the number of school days to boot. Now Governor Deal and the Legislature are set to give our local school boards an additional $550 million per year in funding.

Where will public school boards spend these additional taxpayer funds? Pretend you’re a student and complete the following sentence: Those who cannot remember the past … Put another way: If history is any guide, Georgia’s teachers, parents and taxpayers may not be happy with their answer.

Scafidi’s “staffing surge” research is available at www.edchoice.org/Research/National-Research.

Data broken down by school system is available in PDF or spreadsheet format.

Benjamin Scafidi is a professor of economics at Georgia College and a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. The views expressed here are his own. The Foundation is an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.)

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (February 21, 2014). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.