Work requirements for able-bodied welfare recipients is a good thing.

By Benita M. Dodd

To hear progressive groups tell it, states are hurting low-income Americans by requiring “food stamp” recipients to find work or face three-month limits on receiving benefits.

Many being forced off the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are unable to prove that they are disabled and need continued assistance, goes the mantra, and anyone urging these individuals off the program and into jobs has no compassion for these hapless, helpless, poor Americans.

The narrative is far from the truth. Requiring able-bodied adults without dependents at home to work provides a helpful, productive path to self-sufficiency.

Time limits are nothing new to SNAP, which “helps low-income individuals and families purchase food so they can obtain a nutritious diet.” Limits were established in 1996, when the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act made most noncitizens ineligible for SNAP and required many adults ages 18-49 without disabilities in childless households to work or face time limits on receiving benefits.

Eligibility was restored to noncitizens, but able-bodied adults still are restricted to three months of SNAP benefits in three years unless they meet the work requirements. They must work at least 80 hours per month, participate in qualifying education and training, or participate in “workfare” – unpaid work through a special state-approved program. For workfare, the amount of time worked depends on the amount of benefits received each month. They could also participate in a SNAP employment and training program.

In 2009, during the economic downturn, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (the Obama administration’s federal stimulus) allowed states to suspend time limits through September 2010. Most states extended the waivers; there was a 19 percent increase in eligible households receiving benefits from 2010-2015.

he economic tide has turned, however. The unemployment rate in Georgia, at a record 10.5 percent in December 2010, was at 4.9 percent in May this year. When the waivers began to expire in 2015, states had to reinstate time limits and work requirements.

he economic tide has turned, however. The unemployment rate in Georgia, at a record 10.5 percent in December 2010, was at 4.9 percent in May this year. When the waivers began to expire in 2015, states had to reinstate time limits and work requirements.

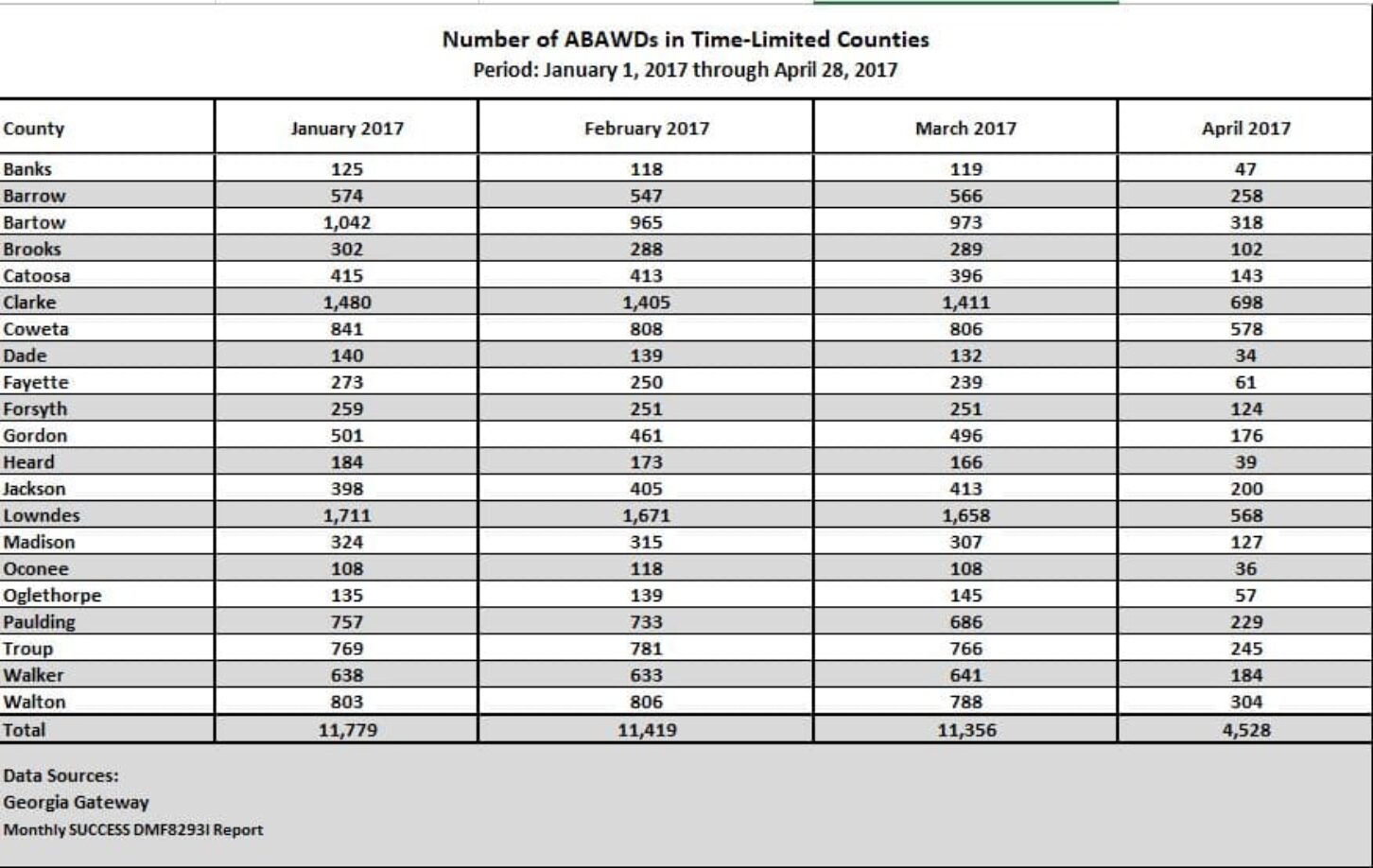

In January 2016, Georgia ended the waiver in Gwinnett, Hall and Cobb counties. By April, the three counties had seen a 58 percent decrease in the rolls of the covered population. In 2017, the waiver ended in another 21 counties. By April, those rolls had dropped a whopping 62 percent.

Did some recipients not have the wherewithal to justify continued benefits without working? Probably. Of course, one could argue these individuals had the wherewithal to apply for benefits initially. It could also be argued progressive organizations do them a disservice by suggesting SNAP beneficiaries are not smart enough to justify continued assistance.

Is the sudden drop the result of welfare “fraud”? Not likely. Welfare frauds exists, of course, and should be punished, but that’s an overused stereotype. When people start seeing programs as an ongoing entitlement instead of a temporary benefit, they get comfortable receiving them and reluctant to relinquish the “free money;” they don’t consider it cheating.

More likely, the vast majority of recipients were simply unable to justify continued benefits. On the positive side, with fewer people to manage, caseworkers can focus attention on those who really need help.

The best welfare program is one that succeeds to the point of being superfluous. SNAP, unfortunately, has mushroomed and more than doubled in cost over the past 10 years. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, SNAP spent $30.4 billion in 2007 to serve 26.5 million people. It spent $69.6 billion in 2015 to serve 45.8 million people; that dropped to $66.5 billion for 44.2 million in 2016.

SNAP is not a gift. It’s a safety net, not a hammock. It’s foolish to make people comfortable taking taxpayer dollars from other working people. There is an obligation to help them up and out of the program and toward self-sufficiency, to reinforce the dignity and happiness found in gainful employment, and to help create positive, motivated role models in the community. Now that the economy and job market have recovered, able-bodied adults who are able to earn a living should be working.

Benita Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (July 14,2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.

By Benita M. Dodd

To hear progressive groups tell it, states are hurting low-income Americans by requiring “food stamp” recipients to find work or face three-month limits on receiving benefits.

Many being forced off the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are unable to prove that they are disabled and need continued assistance, goes the mantra, and anyone urging these individuals off the program and into jobs has no compassion for these hapless, helpless, poor Americans.

The narrative is far from the truth. Requiring able-bodied adults without dependents at home to work provides a helpful, productive path to self-sufficiency.

Time limits are nothing new to SNAP, which “helps low-income individuals and families purchase food so they can obtain a nutritious diet.” Limits were established in 1996, when the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act made most noncitizens ineligible for SNAP and required many adults ages 18-49 without disabilities in childless households to work or face time limits on receiving benefits.

Eligibility was restored to noncitizens, but able-bodied adults still are restricted to three months of SNAP benefits in three years unless they meet the work requirements. They must work at least 80 hours per month, participate in qualifying education and training, or participate in “workfare” – unpaid work through a special state-approved program. For workfare, the amount of time worked depends on the amount of benefits received each month. They could also participate in a SNAP employment and training program.

In 2009, during the economic downturn, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (the Obama administration’s federal stimulus) allowed states to suspend time limits through September 2010. Most states extended the waivers; there was a 19 percent increase in eligible households receiving benefits from 2010-2015.

he economic tide has turned, however. The unemployment rate in Georgia, at a record 10.5 percent in December 2010, was at 4.9 percent in May this year. When the waivers began to expire in 2015, states had to reinstate time limits and work requirements.

he economic tide has turned, however. The unemployment rate in Georgia, at a record 10.5 percent in December 2010, was at 4.9 percent in May this year. When the waivers began to expire in 2015, states had to reinstate time limits and work requirements.

In January 2016, Georgia ended the waiver in Gwinnett, Hall and Cobb counties. By April, the three counties had seen a 58 percent decrease in the rolls of the covered population. In 2017, the waiver ended in another 21 counties. By April, those rolls had dropped a whopping 62 percent.

Did some recipients not have the wherewithal to justify continued benefits without working? Probably. Of course, one could argue these individuals had the wherewithal to apply for benefits initially. It could also be argued progressive organizations do them a disservice by suggesting SNAP beneficiaries are not smart enough to justify continued assistance.

Is the sudden drop the result of welfare “fraud”? Not likely. Welfare frauds exists, of course, and should be punished, but that’s an overused stereotype. When people start seeing programs as an ongoing entitlement instead of a temporary benefit, they get comfortable receiving them and reluctant to relinquish the “free money;” they don’t consider it cheating.

More likely, the vast majority of recipients were simply unable to justify continued benefits. On the positive side, with fewer people to manage, caseworkers can focus attention on those who really need help.

The best welfare program is one that succeeds to the point of being superfluous. SNAP, unfortunately, has mushroomed and more than doubled in cost over the past 10 years. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, SNAP spent $30.4 billion in 2007 to serve 26.5 million people. It spent $69.6 billion in 2015 to serve 45.8 million people; that dropped to $66.5 billion for 44.2 million in 2016.

SNAP is not a gift. It’s a safety net, not a hammock. It’s foolish to make people comfortable taking taxpayer dollars from other working people. There is an obligation to help them up and out of the program and toward self-sufficiency, to reinforce the dignity and happiness found in gainful employment, and to help create positive, motivated role models in the community. Now that the economy and job market have recovered, able-bodied adults who are able to earn a living should be working.

Benita Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (July 14,2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.