How’s the Streetcar doing as it enters its third year?

By Benita M. Dodd

Today the city of Atlanta begins Year 3 of operating its much-ballyhooed Atlanta Streetcar System, and so far, all that can be discerned is a lot of bally hooey.

This month, the Atlanta City Council approved the final payment to URS for the design-build of the 2.7-mile Atlanta Streetcar project, making the total payment $61,630,655. That was, according to Public Works Commissioner Richard Mendoza, “$6 million less than URS originally submitted.”

Not exactly. The 2014 URS contract authorized by MARTA (the transit authority designated to receive the $47.6 million federal grant for the Streetcar), was $59 million; the original URS contract, based on the preliminary design, was $52.2 million.

Asked about the project’s full cost, Mendoza told councilmembers, “The entire project came in a tad under $97 million, which was within the original budget.”

Not really. The original budget for the project, as listed in the TIGER federal grant application in 2010, was a capital cost of about $72 million. Annual operation and maintenance (O&M) costs in 2013, when it was originally slated to start running, would be about $1.7 million.

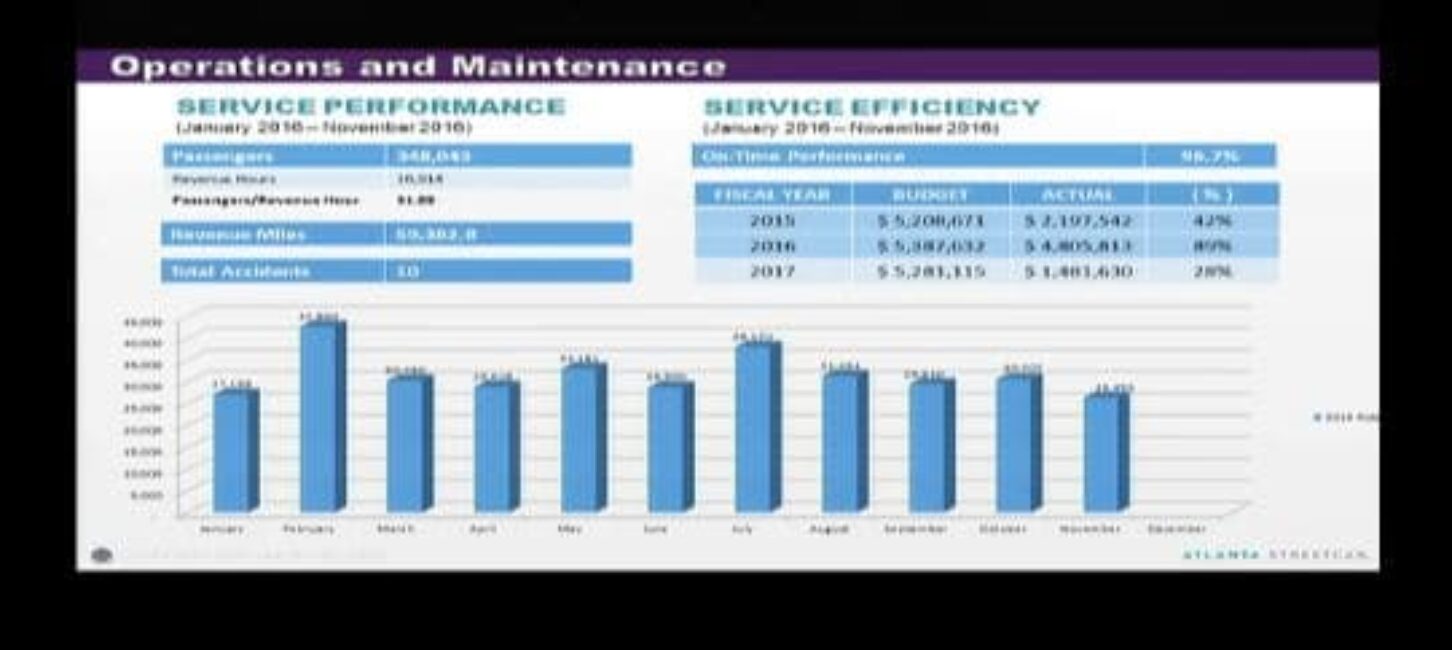

Later, the city projected a cost of about $3.2 million a year to operate the system. Then in February 2016, the city revised that cost to $4.8 million – a 52 percent increase. The city’s FY2017 budget includes nearly $5.3 million for the Streetcar O&M.

As for revenues: The grant application projected $420,000 in farebox revenue for the expected first year of operation (2013), making up 20 percent of O&M costs. In fact, the farebox recovery ratio is just 5.2 percent, as Mendoza told councilmembers on December 14 during his quarterly update on the system.

From January through November 2016, tickets brought in $177,580; by extrapolation, the 2016 farebox will bring in less than $195,000. That’s less than half (46 percent) of the grant application projection.

There were 809,000 passengers in 2015. From January through November 2016, there were just 348,043. The grant application listed projected average weekday ridership at 2,600; but this year (without breaking out weekend ridership) it is 1,462, just 56 percent of that original estimate.

The Streetcar had a late and spotty start, too. After construction and testing delays, operations began on December 30, 2014. It was supposed to offer free rides for three months; in March 2015, the mayor declared it would be free for the entire first year.

Ridership plunged after the $1 fare was implemented on January 1, although it did help reduce the number of homeless riding the vehicles. Fare evasion is a problem: The city reports 53 just percent of riders are paying the fare; hopes are better policing and a newly launched app will improve revenues.

State and federal audits found safety and management problems; in May, the Georgia Department of Transportation threatened to shut down the Streetcar unless corrective action was taken. This month, Mendoza told the Transportation Committee that nine (14 percent) items of 66 on the “Corrective Action Plan” had been completed.

This week, the city announced reduced Streetcar hours for the holiday weekend, “a modified schedule for New Year’s Eve to accommodate large crowds expected to attend holiday events in the downtown area. On Dec. 31 the streetcar will operate from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., and then will resume normal operating hours on Jan. 1, running from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m.”

Reducing hours when tourists are most likely downtown is a far cry from the hype in the grant application: “[I]t will provide connectivity and circulation for the core of the Downtown area of Atlanta, improving accessibility and making it possible to conveniently travel from key destinations and event venues without a car and connecting tourists, residents, students and workers to attractions, jobs and public amenities.”

Unfazed by the dismal results so far, the city has another 22-mile phase under environmental review, planning to leverage November’s transit sales tax proposals that won 72 percent voter approval. Apparently, the project is nowhere near big enough to fail yet. The biggest tragedy, however, is that in an era of rapidly changing technology, Atlanta residents will be stuck with this transit from a bygone era for another 40 years.

Benita Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (December 30, 2016). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.

By Benita M. Dodd

Atlanta’s Streetcar System, three years later, still is nothing to brag about.

Today the city of Atlanta begins Year 3 of operating its much-ballyhooed Atlanta Streetcar System, and so far, all that can be discerned is a lot of bally hooey.

This month, the Atlanta City Council approved the final payment to URS for the design-build of the 2.7-mile Atlanta Streetcar project, making the total payment $61,630,655. That was, according to Public Works Commissioner Richard Mendoza, “$6 million less than URS originally submitted.”

Not exactly. The 2014 URS contract authorized by MARTA (the transit authority designated to receive the $47.6 million federal grant for the Streetcar), was $59 million; the original URS contract, based on the preliminary design, was $52.2 million.

Asked about the project’s full cost, Mendoza told councilmembers, “The entire project came in a tad under $97 million, which was within the original budget.”

Not really. The original budget for the project, as listed in the TIGER federal grant application in 2010, was a capital cost of about $72 million. Annual operation and maintenance (O&M) costs in 2013, when it was originally slated to start running, would be about $1.7 million.

Later, the city projected a cost of about $3.2 million a year to operate the system. Then in February 2016, the city revised that cost to $4.8 million – a 52 percent increase. The city’s FY2017 budget includes nearly $5.3 million for the Streetcar O&M.

As for revenues: The grant application projected $420,000 in farebox revenue for the expected first year of operation (2013), making up 20 percent of O&M costs. In fact, the farebox recovery ratio is just 5.2 percent, as Mendoza told councilmembers on December 14 during his quarterly update on the system.

From January through November 2016, tickets brought in $177,580; by extrapolation, the 2016 farebox will bring in less than $195,000. That’s less than half (46 percent) of the grant application projection.

There were 809,000 passengers in 2015. From January through November 2016, there were just 348,043. The grant application listed projected average weekday ridership at 2,600; but this year (without breaking out weekend ridership) it is 1,462, just 56 percent of that original estimate.

The Streetcar had a late and spotty start, too. After construction and testing delays, operations began on December 30, 2014. It was supposed to offer free rides for three months; in March 2015, the mayor declared it would be free for the entire first year.

Ridership plunged after the $1 fare was implemented on January 1, although it did help reduce the number of homeless riding the vehicles. Fare evasion is a problem: The city reports 53 just percent of riders are paying the fare; hopes are better policing and a newly launched app will improve revenues.

State and federal audits found safety and management problems; in May, the Georgia Department of Transportation threatened to shut down the Streetcar unless corrective action was taken. This month, Mendoza told the Transportation Committee that nine (14 percent) items of 66 on the “Corrective Action Plan” had been completed.

Streetcar ridership has been declining since February’s high, according to the city of Atlanta.

This week, the city announced reduced Streetcar hours for the holiday weekend, “a modified schedule for New Year’s Eve to accommodate large crowds expected to attend holiday events in the downtown area. On Dec. 31 the streetcar will operate from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., and then will resume normal operating hours on Jan. 1, running from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m.”

Reducing hours when tourists are most likely downtown is a far cry from the hype in the grant application: “[I]t will provide connectivity and circulation for the core of the Downtown area of Atlanta, improving accessibility and making it possible to conveniently travel from key destinations and event venues without a car and connecting tourists, residents, students and workers to attractions, jobs and public amenities.”

Unfazed by the dismal results so far, the city has another 22-mile phase under environmental review, planning to leverage November’s transit sales tax proposals that won 72 percent voter approval. Apparently, the project is nowhere near big enough to fail yet. The biggest tragedy, however, is that in an era of rapidly changing technology, Atlanta residents will be stuck with this transit from a bygone era for another 40 years.

Benita Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (December 30, 2016). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.